The 1990s

During the 1990s, the Israeli cinema refrained from a direct treatment of current social and political events. In reaction to, and contrary to historical events such as the first Intifada (1987-1993) and the assassination of Prime Minister Rabin (1995), it preferred the subjective life experiences over the national narrative, and concentrated on individual identities and (thus far) unnoticed communities.[1] As it avoided analyzing historical events or discussing political stances, Israeli cinema of the 1990s makes room for personal deliberations.[2] Although Time for cherries (Haim Bouzaglo, 1991) does deal with the first Lebanon War (1982-1985), it steers away from realism to post-modernist representation of reality. Instead of dramatizing the real war, it is conducted as a series of staged performances that blur the difference between reality and artistic representation; reality and its representation become one.[3]

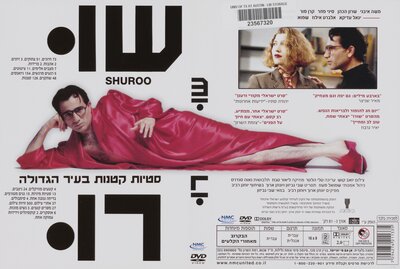

As a somewhat escapist alternative, the cinematic landscape of the 1990s is comprised either of metropolitan spaces, where the hegemonic Sabra[4] becomes a foreigner in his/her own ‘land,’ – or of the periphery, where new non-hegemonic imageries of the Israeli society are being formed. Protagonists cocoon themselves within an ‘internal exile,’ and experience post-modern existential confusion.[5] The lookout (aka Shuroo, Savi Gabizon, 1990), is an offbeat comedy about a conman who becomes a guru overnight, finding himself surrounded by a group of people who are drawn to him in search of meaning of their urban, Tel-Avivian existence. Amazing Grace (Amos Guttman, 1992) describes gay life in Tel Aviv, while offering a universal understanding of the human existence wherever it is. Song of the siren (Eitan Fox, 1994) is an urban romcom that takes place in Tel Aviv during the 1991 Gulf War,[6] where the war is always in the background but the protagonists are occupied with their love life. Life according to Agfa (Assi Dayan, 1992) is an apocalyptic fantasy that takes place at a Tel-Avivian dense pub, where the full gamut of Israeli society gathers together – Ashkenazi and Mizrahi, Jews and Arabs, citizens and soldiers – with a catastrophic end to a society that cannot contain its controversies anymore.

Many directors of the 1990s chose to leave the metropolitan, and explore remote areas and non-conventional topics. Daniel Wachsmann’sThe appointed (1990) takes place in a mystical community of ultra-orthodox Jews in the Galilee (northern Israel). Hagai Levi’s August snow(1993) tells a love story within the Jewish-Italian community of Jerusalem, questioning religious beliefs and secularism. Eitan Green’s American citizen (1992) examines a male friendship between an Israeli sports journalist in a small southern town and an American basketball player who was hired to play at the local team.

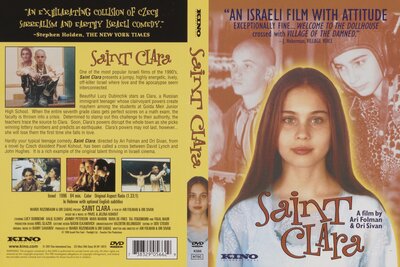

While distancing from the political arena, cinematic expressions of the 1990s do not completely ignore Israeli reality, but rather explore ethnic groups that were not treated cinematically thus far, such as Russian immigrants, or re-discover earlier ‘others,’ such as Mizrahi Jews. A direct result of the fall of the Soviet Union (USSR) was that an unprecedent number of Jews immigrated to Israel, impacting the social, cultural, and political spheres.[7] Under Western Eyes (Joseph Pitchhadze, 1996) explores the Israeli Russian community and its traumatic identity crisis. Yana’s friends (Arik Kaplun, 1999) criticizes the way hegemonic Israelis treated ‘the Russians’ in that time period. Saint Clara (Ori Sivan and Ari Folman, 1996)[8] offers a unique point of view on the Israelis’ reaction to the ‘new others’ among them; in peripheral, fantastic scenery, it shows the intolerance and extreme nihilism that might lead the torn-apart Israeli society into calamity, suggesting Russian otherness as a savior.[9] Sh'Chur (Shmuel Hasfari, 1994), a semi-autobiographical film,[10] tells the story of a Mizrahi family and its reliance on traditional, mystical spells, while questioning personal identity and feminism. Now considered a canonical cinematic text,[11] it redefined the identity politics in Israeli cinema.

[1] Munk, Ya’el. Golim bi-gevulam : ha-ḳolnoʻa ha-Yiśre'eli be-mifneh ha-elef. Universitah ha-petuhah, Ra’ananah, 2012 [Hebrew].

[2] Yitshhak Tsepel Yeshurun’s Green Fields (1989) and Avram Hefner’s What happened? (1988) were the only films at that time period that directly dealt with the first Intifada. Rabin’s assassination was first analyzed on screen only 20 years later, in 2015.

[3] Two additional war movies were released in 1991: Eran Riklis’s Cup final, taking place during the first Lebanon War (1982-1985) and Uri Barabash’s The war after, reckoning with the traumas of the 1973 Yom-Kippur war.

[4] Sabra is a Jewish person born in Israel, either before or after 1948. The term alludes to Tsabar (prickly pear) – “a tenacious, thorny desert plant, with a thick skin that conceals a sweet, softer interior. The cactus is compared to Israeli Jews, who are supposedly tough on the outside, but delicate and sweet on the inside. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sabra_(person)

[5] Munk (2012), 24-29. [Hebrew].

[6] Cinematic adaptation of a book by same title by Irit Linur (1991).

[7] Almost 1,000,000 Russian Jews immigrated to Israel between 1989 and 2000. See also Maltz, Judy. One, two, three, four – we opened up the Iron Door. Haaretz, February 5, 2015.

[8] Its screenplay is based on the novel The Ideas of Saint Clara by Pavel Kohout (1980).

[9] Munk (2012), 122-124. [Hebrew].

[10] Written by Hannah Azuolay-Hasfari.

[11] Ibid., 138.