Conflicting Claims Lead to Wars (1821-1845)

Increasing tensions characterized the first half of the nineteenth century in the U.S.-Mexico border regions. The U.S.’s western expansion led to encroachment and settlement in Mexican-claimed territory and bred hostilities in all facets of U.S.-Mexican relations. A major point of contention was the status of Texas, a heavily Anglo settled region of Mexico. Texans, Mexicans, and Americans pursued their interests often in conflict with one another. The U.S.’s pursuit of Manifest Destiny, Mexico’s internal and external struggle to maintain its borders, and Texans' efforts to import U.S. slavery into Mexico, where it was illegal, created key points of conflict that would boil over into two full-fledged wars.

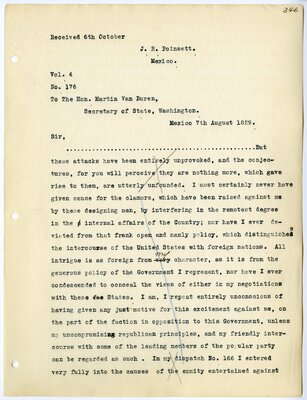

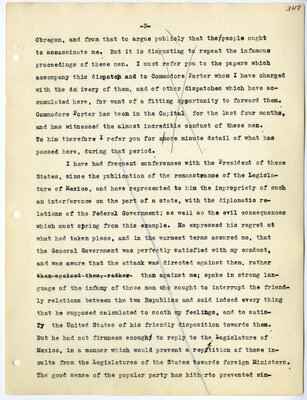

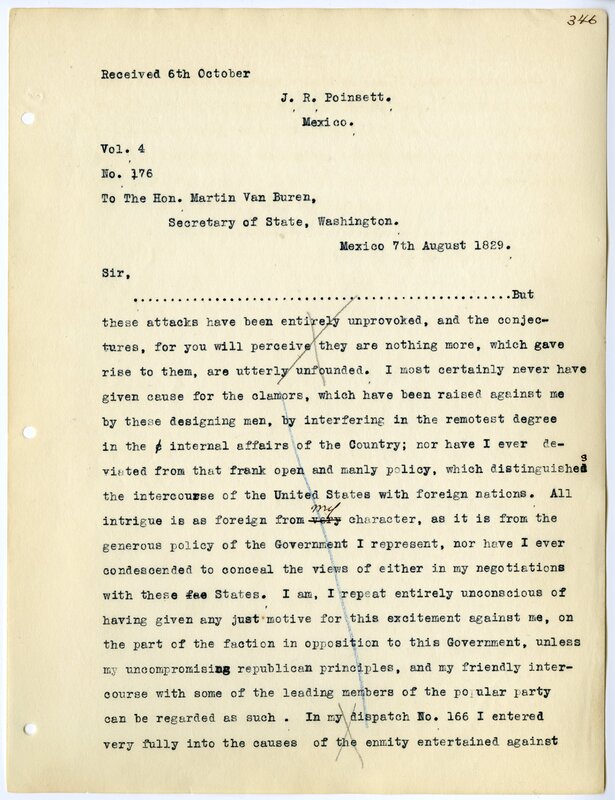

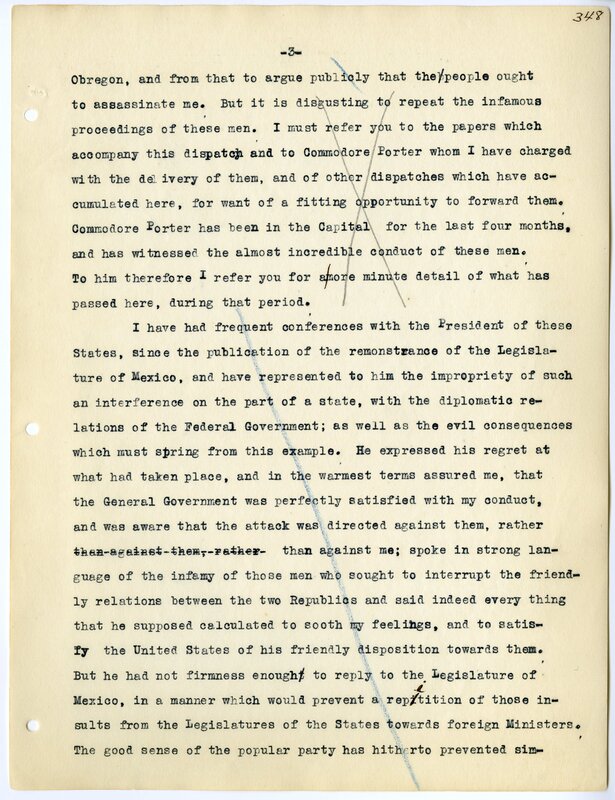

Poinsett Transcription

This typewritten source evidences how an early 20th-century historian tried to make sense of 19th-century U.S.-Mexican relations.

In 1920, Justin Harvey Smith was the first historian to win a Pulitzer Prize for his book on the US-Mexican War. Among his papers, which were donated to the Benson, is this transcription of correspondence between the U.S. ambassador to Mexico, J. R. Poinsett, to the U.S. Secretary of State (and future president) Martin Van Buren. Dated August 1829, the document outlines the instability of the Mexican republic and the worsening of U.S.-Mexican relations. The letter demonstrates how Mexican Conservatives did not trust the United States. The current administration, controlled by the Liberal party, was no friendlier. So concerned was Poinsett about a general anti-U.S. sentiment in Mexico that he worried about being a target for assassination. Poinsett doubts the stability of the young Mexican Republic, citing the alarmingly quick fall from power suffered by Mexican President Guadalupe Victoria in 1829.

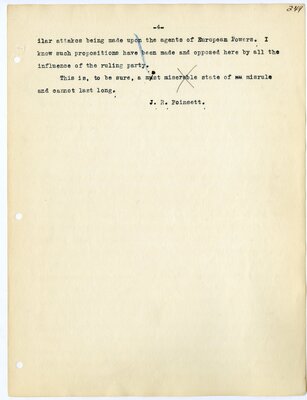

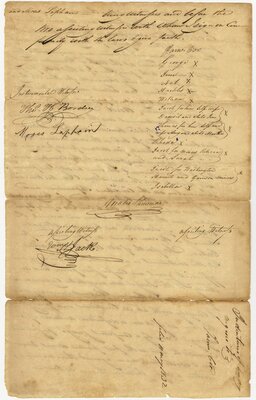

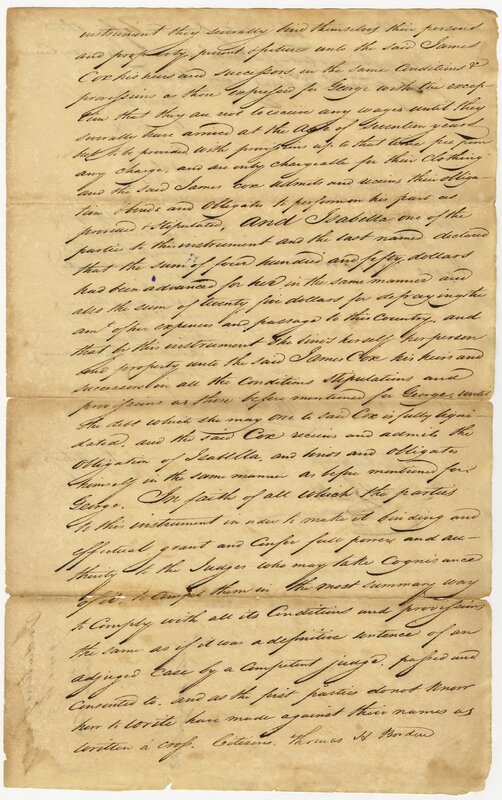

Agreement to Indenture Eighteen Negroes to James Cox of Texas

The "Xs" marked next to each of the eleven named enslaved individuals suggest the people signing off on this contract did not know how to write, much less how to sign their own names. James Cox, an Anglo-American slave-owner residing in Mexican-controlled Texas, bypassed Mexico’s ban on the practice of slavery through coerced contracts of indentured servitude like this one. Cox, like many other American settlers in Texas, was determined to preserve the system of human bondage that Texan and Mexican officials had allowed to take root in the region, despite Mexico's 1829 law abolishing slavery. The blood of Texan and Mexicans would dot the Mexican landscape as the battle for the preservation of slavery intensified.

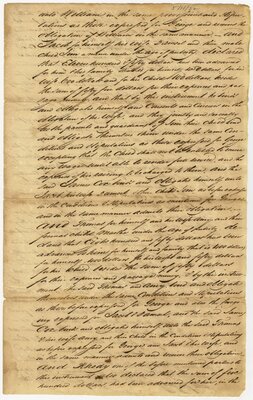

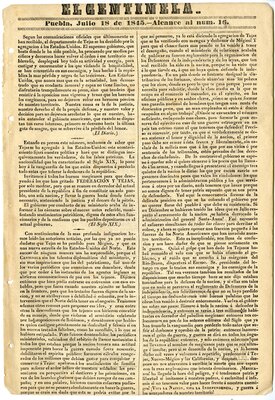

El Centinela

The browning of this newspaper reflects its age; it is almost 180 years

old. Townspeople likely gathered in Puebla’s town square to read this July 18, 1845 edition of El Centinela which warns against the American annexation of Texas and prophesies the takeover of the rest of Mexico’s northwest territory. There is palpable anger in the text towards the United States. Mexican honor and land are at stake as the U.S. seeks to gobble up more territory. The author wants to rally the Mexican people to defend their homeland. The views expressed represent a time when Mexico was preparing for war against the United States. As we know, the author was correct in his assertions that there would be a war, and Mexico would lose more than Texas as the U.S. expanded.