Global/Modern Latin America

The long 19th century in Latin America saw the global transformation of technology and modes of communication that helped contribute to emerging ideas of modernity, national identity, and changes in consumer patterns in Latin America. While photography captured the gendered dimensions of textile production in Mexico around 1910, telegraphs communicated the urgency of revolutionary upheaval. Print culture advancements allowed colored print images wrapped around chocolate bars in Spain to serve as propaganda on a lost war and allowed political cartoons to communicate the negative effects of progress. Global connections allowed Scottish scientists to create plans to transform Chile’s economy and environment through fish-farming. The primary sources in this section of the exhibit provide glimpses into how information and news were conveyed in Latin America throughout the long 19th century, along with how the medium of the source affects the message. Taken together, they show how emerging notions of modernity and technological advances combined to create new ideologies and practices in a modern Latin America.

"In a Mexican Patio making drawnwork"

In this 1904 photograph taken by Abel Briquet in Mexico, young women wearing dresses reminiscent of contemporary European styles fabricate handcrafted textiles while an older woman supervises. The image, taken with modern photographic technology, reveals tensions between working women and traditional gender expectations in early 20th Century Porfirian Mexico. At one level, the presence of women in production challenges assumptions about men’s predominance in modernization. Women’s labor was essential to modern economic and industrial development precisely at a time more and more people consumed goods. At the same time, that they are nicely dressed and supervised suggests Mexican society worried about women’s respectability. Additionally, these women wear European style dresses, suggesting Mexico increasingly linked its ideas about modernity and respectability to European models. The photograph therefore captures the social tensions concerning women working outside the home at a time when their labor increasingly contributed to Mexican processes of modernization.

"The Situation"

The cartoon, "La Situación," visualizes Progressive Reforms as a destructive train driven by the "Supreme Government" that tramples the people in it’s way. Between 1854 and 1861there were a series of Reforms Laws that were established as progressive movements to help lower class Mexicans and reduce the influence of the Church. But in this depiction of historical events, “Liberty”, while chasing down the church with his spear, tramples “the society”. This cartoon, sampled from an 1856 newspaper called Padres Del Agua Fria, portrays a backlash against the La Reforma period under President Santa Anna. Political cartoons were an integral part in the modernization of Latin America, and they helped contribute to it’s democratic identity. In this case, the reforms negatively affected portions of “the society” that they were supposed to be helping. "La Situación" was printed to represent a popular opinion from those who saw these reforms as tools used to establish a powerful government that undermined liberty in its efforts to weaken the Church.

"Report by Pisciculturist W. Anderson Smith on the Introduction of Salmon in Chile," title page

The government document titled “Report of the Farmer on Introduction of Salmon in Chile” details instructions given to the Chilean Government by a Scottish fisheries expert to establish the fish farming industry in Chile in the late 19th century. The stocking of Salmon in Chilean waters allowed for the fish to become synonymous with the boom of industry in Chile. This document allows for comparisons to other Latin American nations by looking into what developments of industry were seen as steps towards modernity. Chile saw establishing a salmon farming industry as modern as it was predicted to boost economic opportunity as Chile entered the 20th century. Salmon are still a crucial Chilean symbol as it is currently the second biggest export of Chile, having such importance that a UN case study detailed the economics of the industry. As important as the industry continues to be for the country, it currently carries negative connotations as being damaging in terms of ecological effects.

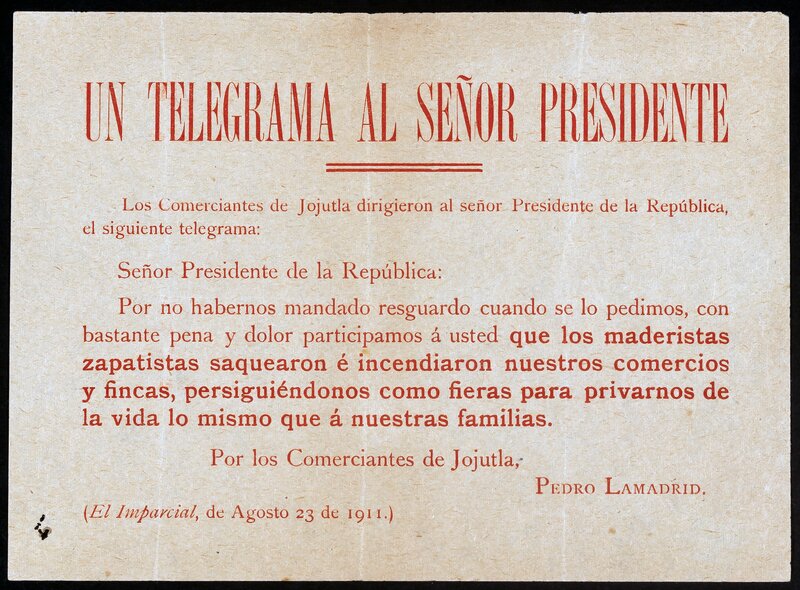

"A Telegram to Mr. President"

This short, typewritten telegram printed in red ink was written during the Mexican Revolution and describes a grievance by Morelos merchants to Francisco León de la Barra, the interim president assigned by dictator Porfirio Díaz after his resignation. Sent in August of 1911, the grievance portrays sorrowful shopkeepers and farmers informing de la Barra that rebel forces under Emiliano Zapata and Francisco Madero, known as “Zapatista Maderistas”, raided the merchants for the purpose of reclaiming hacienda land. This uprising was rooted in the desire for agrarian reform by many villagers given how powerful entrepreneurs forced villagers of common lands for the purpose of furthering their businesses during the Porfiriato. The telegraph was made possible because of the infrastructure built from the time of Benito Juarez and further developed under Porfirio Díaz. Modern communications technology reveals the immediacy of the violence unleashed during the Mexican Revolution.

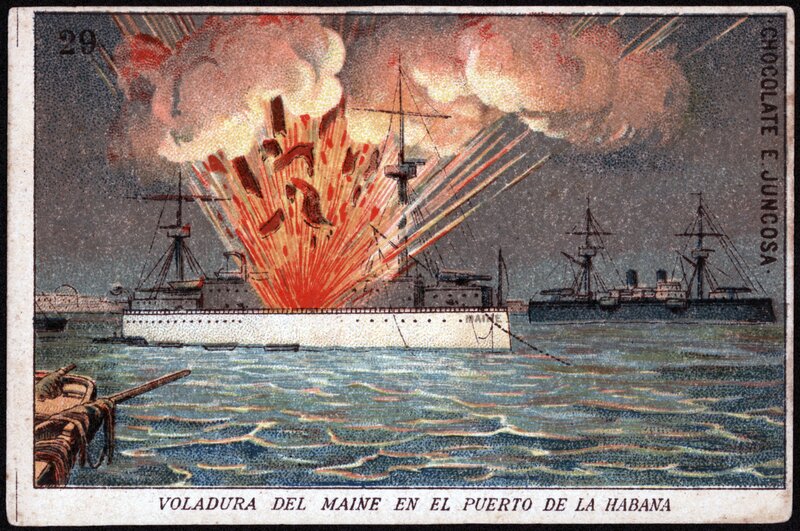

"Blasting of the Maine in the Port of Havana"

The trading card in the Chocolate E. Juncosa wrapper depicts the explosion of an American naval ship, the USS Maine. This attack in the Havana Harbor marked a turning point in the fates of Spain and Cuba. It foreshadows the conclusion of Cuba’s long journey toward independence and the beginning of the end of Spain’s imperial power. Because the cards were produced in Barcelona a decade after the attack, the illustration of the event comes from a biased standpoint. The purpose was to salvage the Spanish’s image of their country after being defeated. The card has no people or boats in the same vicinity as The Maine leaving the viewer with the visual imprint that no Spaniard was around when tragedy struck. The distancing of the Spanish from this event is a form of propaganda persuading the public to believe that Spain shouldn’t take the blame for the US’ entry in the war.