Justice For Farah

On the heels of the Economy Furniture Company Strike resolution, 4000 Farah garment workers walked off their jobs in El Paso, San Antonio, and Las Cruces to protest low wages, unrealistic quotas, inadequate pension benefits, and the right to unionize in May 1972.[1] However, two characteristics set the Farah strike apart. The first was its scale: in the years before the strike, the Farah Manufacturing Company was the second largest employer in El Paso, a city known as the “Jeans Capital of the World.”[2] The second was the leadership role Chicana women played in the labor mobilization and the victories it claimed. This section will look at these differences.

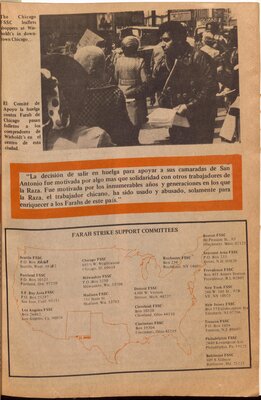

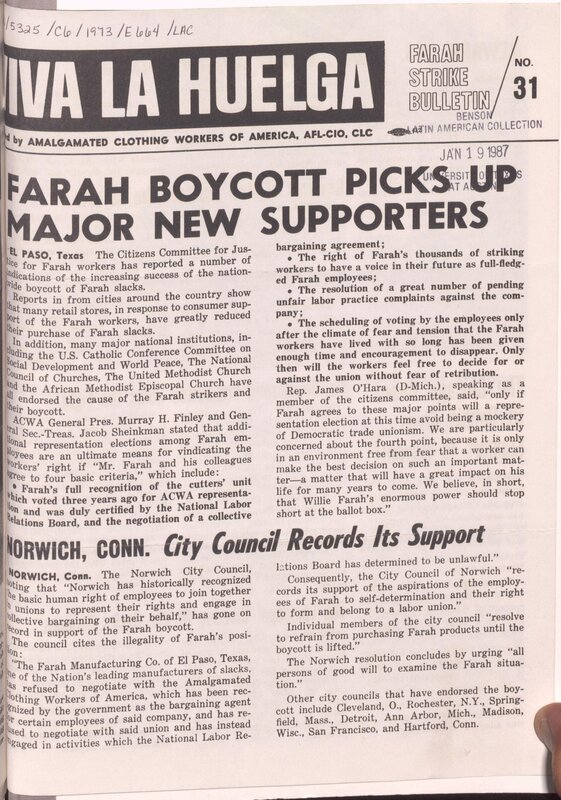

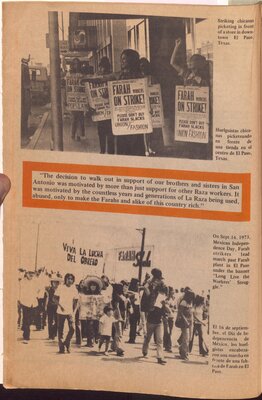

As the nationwide boycott of Farah products took off and demands for justice for Farah workers reverberated across the United States. Pamphlets, newsletters, flyers, and picket signs with slogans like “Please Don’t Buy Farah Slacks” and “Boycott Farah Pants” appeared across major urban centers and university campuses. By 1974, the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (ACWA), which represented the Farah garment workers, had forty union representatives in more than sixty cities working on boycott campaigns against Farah products, resulting in an estimated 20 million-dollar loss for the company.[3]

Solidarity on a national level was key. This was especially true in the context of El Paso, a city profoundly shaped by its proximity to the Mexico-US border.[4] At the heart of the Farah movement, El Paso was reputed for its anti-union sentiment, one that was amplified by the paternalistic legacy of Farah CEO and “local hero” Willie Farah. Economic hardship complicated local support for the strike and facilitated the company's campaigns to hire scab workers from the bordering city of Ciudad Juarez.

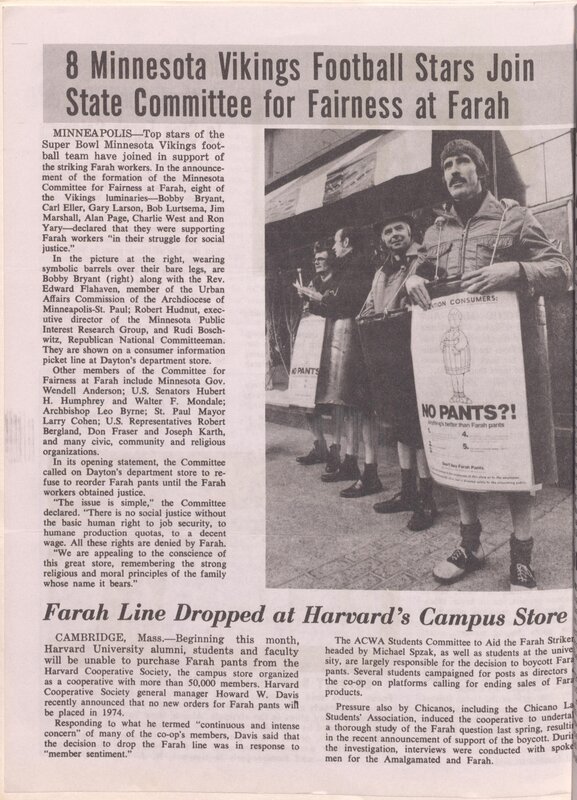

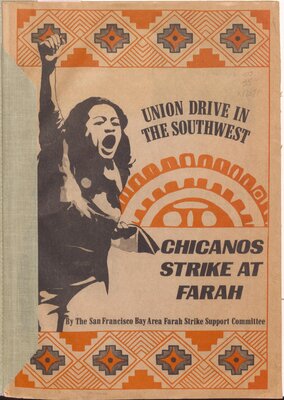

Besides raising funds and organizing strike activities, boycott committees also published newsletters to keep a national audience informed and galvanized. The ACWA’s Víva La Huelga; Farah Strike Bulletin AFL-CIO, and the San Francisco Bay Area Farah Strike Support Committee’s Chicanos Strike at Farah: Union Drive in the Southwest are two examples of bilingual publications specifically focused on disseminating information about the strike. Both show the far-reaching support the Farah movement received across the country in what became broadly understood as a “struggle for social justice.”[5] The solidarity these circulars garnered led to material and political support that sustained strikers on the ground, facilitating the wins workers eventually achieved. If fraught and ultimately short-lived, these wins shook the industrial Anglo elite class in, and beyond, El Paso.

The participation of Mexican American women in Texas labor mobilizations was not new. However, what was unprecedented in the Farah movement was the radical public-facing leadership women assumed.[6] Women, who comprised a significant percentage of industrial textile industry workers in Texas and a majority in border cities like El Paso, made up 85 percent of Farah’s workforce. Almost all were Mexican American.[7] Chicanas joined boycott tours, spoke at strike events, founded the “Farah Distress Fund,” and organized a committee to push for more accountability from the union to the strikers. Through their leadership, Chicanas claimed space and worked to transform the Chicano Movement itself.

In 1974, Willie Farah gave in and the union claimed a win calling an end to the strike and boycott. For many Chicanas, who had experienced an extended economic precarity intensified by gendered responsibilities of childcare, the conclusion was monumental. However, their ongoing struggle to gain a voice within a mainstream labor movement and the continued challenges of maintaining union recognition in a right-to-work state cast a shadow on the victory. Within the decade, these wins were further overshadowed by the economic restructuring of the borderlands spurred by the relocation of textile factories across the border to Mexico.

While the strike did not fundamentally change working conditions for Chicana garment workers in El Paso, it gave them a voice and the experience to continue to fight for justice as workers and as women. The lessons learned in turn inspired decades of women-led labor organizing in the region. For example, some Chicanas of Farah went on to join labor organizing campaigns across the state, such as the Texas Farm Workers Organizing Committee.[8]

Footenotes:

[1] Ruíz Vicki and Sánchez Korrol Virginia, Latinas in the United States: A Historical Encyclopedia (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2006); Laurie Coyle, Gail Hershatter, and Emily Honig, “TSHA | Farah Strike,” www.tshaonline.org, 1995, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/farah-strike.

[2] Gabriel Solis, “Farah’s 50 Years Later,” Spectre Journal, June 2022.

[3] Laurie Coyle, Gail Hersbatter, and Emily Honig, “Women at Farah: An Unfinished Story,” in A Needle, a Bobbin, a Strike: Women Needleworkers in America, ed. Joan M. Jensen and Sue Davidson (Temple University Press, 1984), 251.

[4] Ruíz and Sánchez, Latinas in the United States: A Historical Encyclopedia, 249.

[5] “8 Minnesota Vikings Football Stars Join State Committee for Fairness at Fara,” Víva La Huelga; Farah Strike Bulletin Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, AFL-CIO., (1973).

[6] One notable exception is Indigenous woman, labor organizer, and member of the Communist Party, Emma Tenayuca (1916-1999) who garnered national attention as a leader in the Pecan Sheller’s Strike of 1938 in San Antonio. Zaragosa Vargas, “Tejana Radical: Emma Tenayuca and the San Antonio Labor Movement during the Great Depression,” Pacific Historical Review 66, no. 4 (November 1997): 553–80, https://doi.org/10.2307/3642237; Yolanda Hinojosa, “Tenayuca, Emma,” in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Latinos and Latinas in the United States (Oxford University Press, 2005).

[7] Ruíz and Sánchez, Latinas in the United States: A Historical Encyclopedia, 249.

[8] Coyle, Hersbatter, and Honig, “Women at Farah: An Unfinished Story,” 261