Central America as a Catalyst for Latin American Identity Formation

Central America in the 19th century was pivotal in shaping a modern Latin American identity. With the decree abolishing slavery in 1824, it became the first region outside Haiti and the Dominican Republic to abolish the institution, propelling proponents of political liberalism to insist on further reforms, such as the separation of Church and State. As these documents show, Central America, most notably Guatemala, offered asylum for religious leaders persecuted in their home countries for insisting on the need for Catholic morality in politics, most notably Mexican priests. In 1856, U.S. filibuster William Walker invaded Nicaragua, an invasion that El Salvador and other Central American countries denounced diplomatically and defeated militarily. Their criticisms of US and European incursions were amplified through the unifying regional identity of Latin America. Concurrently, Colombia, in the midst of nation-building, wrote and rewrote numerous versions of its constitution, resulting in a tapestry of debates concerning slavery, religion, interventionism, social dynamics, and ideology woven within experimental 19th-century legal frameworks, reflecting the changing mentalities of the ruling classes and their allies. Through the examination of various secondary sources, we are able to contextualize these moments within a broader picture that emphasizes the shifting perspective on modernity within the region. By analyzing the interplay of legal development and societal ideologies, we are able to truly understand the complex dynamics that drove the construction of Central American identity during this crucial era.

Abolition in Central America

This printed decree, written by Marcial Zebadúa, abolished slavery in the newly formed United Provinces of Central America, a union of states which lasted from 1823 to 1840 and included modern day Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Costa Rica, and Nicaragua. The 1824 abolition of slavery in the United Provinces of Central America was a landmark achievement, as these were the first states in Latin America outside of Haiti and the Dominican Republic to officially abolish slavery.[1] Although this is one of many decrees issued in the early days of the federal republic, it nevertheless remained in effect in all the countries that emerged from the dissolution of the United Provinces. The United Provinces of Central America took the first steps in removing slavery from the Latin American economy and modernizing the region on their own terms. Though there were attempts to reestablish slavery, one of the most notable attempts being that of William Walker in Nicaragua, Latin America continued to push forward toward their own vision of a modern Latin America, a region without slavery and with equal opportunity for all people.

¡A los pueblos del Estado!

This 1857 broadside was written in San Miguel, El Salvador by municipal Mayor, Clemente Jirón, and Cicilio Espinoza, municipal Vice-Secretary. The document announces the results from a vote declaring El Salvador’s support for a Central American united force to end the pirate filibuster led by William Walker that took control over El Salvador’s neighbor, Nicaragua. To add insult to injury, U.S. President Franklin Pierce diplomatically recognized Walker’s pirate government. United States expansionism and European imperialism served as the backdrop to this event that galvanized an alternate republican-based version of political modernity in the region, culminating in the term “Latin America”. This document evinces the Central American community's negative reaction to the filibuster, which was viewed as flagrant malfeasance against their own modernity.[2]

Church and State Dynamics in Mexico

Upon a torn parchment lies a symbol representing an enduring struggle: an opened bible, whispering forgotten truths rests at the bottom. Atop it lies a Bishop’s crozier and sword crossed to guard against unforeseen foes, while a Bishop’s hat and rosary are stationed above it all. The decorated parchment contains a letter penned in 1859 by Bishop Charles María Colina during his exile in Guatemala. Part of a series, the letter was dispatched to Churches throughout Mexico, particularly his former parish, the Diocesis de San Christobal de las Casas. Bishop Colina wrote in response to the Mexican Constitution of 1857 and its aggressive Ley de la Reforma, or Reform Laws aimed at separating Church and State, suppressing monasteries, and seizing Church assets[3]. It serves as a testament to the unstable political landscape of mid-19th century Mexico and the government’s efforts under President Juárez to secularize the state and dimmish the Catholic Church’s influence. Bishop Colina’s exile and correspondence highlight the challenges faced by religious figures amidst shifting political tides[4], how could this ultimately change the dynamic between religion and politics for the better in Mexican society?

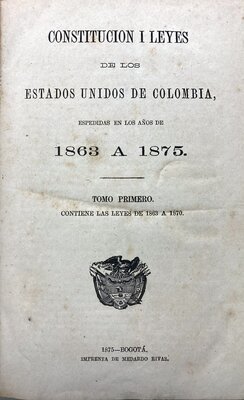

Constitutional Reform in Colombia

Constitucion I Leyes de los Estados Unidos de Colombia, compiled by Colombian politician Medardo Rivas, is a comprehensive collection of living, repealed, and reformed laws enacted by the Colombian Congress from 1863 to 1875, featuring the Constitution of the Union at the beginning. It emerged as a Liberal response to Conservative dominance in the 1850s, which ironically stemmed from Liberal initiatives such as abolishing slavery and introducing universal male suffrage. After the Liberals, led by Governor Tomás Cipriano de Mosquera of Cauca, triumphed in the 1861 Civil War, they established a new, more restrictive constitution granting significant power to the nine newly formed states, which included regions as far North as Panama and enabled them to tailor voting regulations to their preferences. Despite this shift, liberal principles such as the separation of Church and State, inspired by Mexico's La Reforma, persisted, paralleling religious reforms occuring across Latin America. This demonstrates a constant swing between ideological beliefs and opens avenues of potential research regarding how political positions in the nineteenth century affected the formation of Latin American nations.

[1]Schmidt-Nowara, Christopher. Slavery, Freedom, and Abolition in Latin America and the Atlantic World. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2011. Print. https://uconn-storrs.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01UCT_STORRS/1jc3j07/alma9934513463502432

[2] GOBAT, MICHEL. “The Invention of Latin America: A Transnational History of Anti-Imperialism, Democracy, and Race.” The American Historical Review 118, no. 5 (2013): 1345–75. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23784580.

[3] LAZOS, JOHN G. “A Young Bishop, Eleven Music Manuscripts, and a Remote Cathedral Archive: A Mexican Musical Legacy Comes to Light.” Latin American Music Review / Revista de Música Latinoamericana, vol. 32, no. 2, 2011, pp. 240–68. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41348254.

[4] Knowlton, Robert J. “Clerical Response to the Mexican Reform, 1855-1875.” The Catholic Historical Review, vol. 50, no. 4, 1965, pp. 509–28. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25017503.