Modernity in Practice: Railroads, Relics, and Regalia

Following the US-Mexican War (1848), people in Mexico increasingly lived through the effects of globalization and industrialization, impacting how they chose to represent themselves and their national identities. Railroads were both a symbol and a material reality that increasingly transformed local landscapes as they connected their inhabitants to global economies. Mexico’s first railroad line constructed in 1850 may have been short. Still, it set in motion the national and international capital that culminated in railways crossing Mexico from the Atlantic to the Pacific by the time of the Porfiriato (1870s-1910). Porfirio Diaz’s government tied trains to a new national identity just as they appropriated indigenous relics as tokens of the nation’s rich past. This modern Mexican identity posited scientific advances and contemporary constructions, such as archaeology, against the backdrop of Mexico’s glorious indigenous history. One result was that, while some indigenous communities were increasingly dispossessed of their lands, others became more interconnected to domestic and international markets through railroads. The merchant women of Tehuantepec on the Pacific coast profited from these new markets, which, in turn, allowed them the resources to make opulent dresses made of expensive fabrics inspired by traditional dress. Their clothing served as an identity piece and began circulating throughout the nation to be worn by more recognizable cultural figures. The broadside, infographic, and photograph below challenge viewers to explore how different people in Mexico reconciled questions of modern progress with their indigenous past (and present).

Contributors:

Aidan Dresang, Justice Morris, Leah Pawelek

Primer camino de fierro en la República Mexicana

This broadside announces the completion of the first railroad in Mexico which spanned 8.2 miles from Veracruz to El Molino. Measuring approximately three by four feet, the poster announces the train’s operation with nationalistic pride—the same nationalism is reflected by the train line’s inauguration date of September 16, 1850, which is the anniversary of Mexico’s independence. Publicity for the railroad plays into Mexico’s push to form a new national identity in the wake of the Mexican-American War. The illustration depicts a train traversing the countryside, carrying the beginnings of industrial development and Western-defined progress along with it. Additionally, the poster portrays two trains in considerable detail while the landscape appears to be an afterthought. The text says that the railroad’s construction overcame “the immense difficulties that the terrain and climate of the coast have faced.” This language of industrial dominance over nature situates the railway as a key invention leading to the commodification of land and resources. To many, the railroad represented a triumph in Mexican innovation—the construction feat countering, as the poster says, ‘los maldicientes.’ Notably, however, Mexico’s embrace of railroads did not fully emerge until the 1870s. Why did Mexico’s railroad boom not begin until nearly twenty years after the opening of the El Molino line?

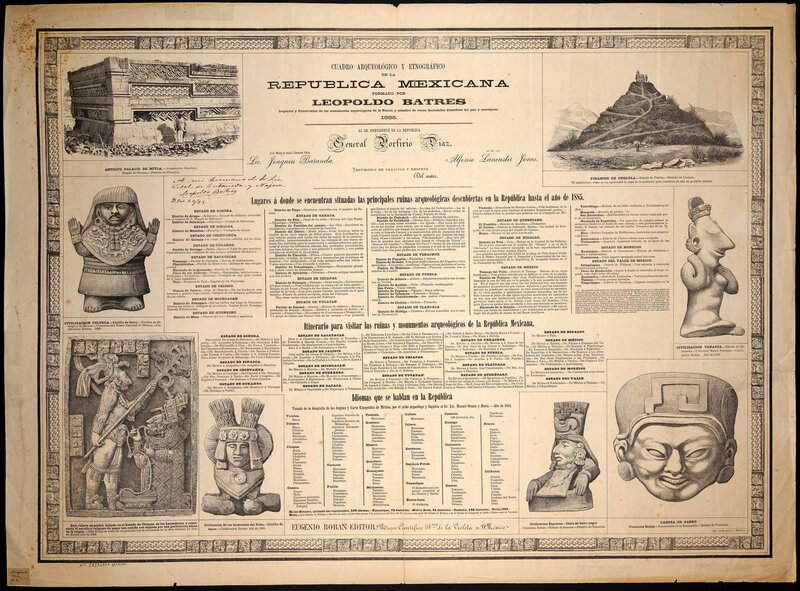

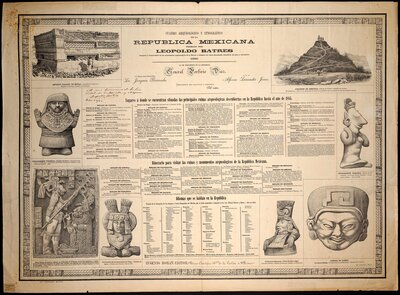

Cuadro arqueológico y etnográfico de la Republica Mexicana por Leopoldo Batres

Endorsed by the Mexican archaeologist Leopoldo Batres, this printed chart, measuring 90 cm X 66 ½ cm, combines images of indigenous sites, structures, and sculptures with details on different regions and cultures, including the Maya, Chinateco, and Mexicano. Porfirio Diaz commissioned this project, which charted a future path for a national identity rooted in a glorious and ancient Indian past while simultaneously disregarding and exploiting the indigenous people still present. For Diaz, archaeology combined the goals of the Mexican government in the late 19th century: create a national identity centered on antiquity and use modern technologies to do so. Notice the top left drawing depicting Milta, however. The drawing reproduces a French photograph taken by Desire Charnay, a photographer sent to help justify French colonization nearly twenty years earlier. Where the image had previously been used for French colonial pretensions, Batres reclaimed it for Mexico.

Tehuantpec woman, velvet and gold [dress], undated

A Tehuantepec woman stands confidently in front of the camera. Her eyes do not meet our gaze, but her attire does. This photograph, taken in the early twentieth century, gives insight into the fashion predating the Mexican Revolution. Tehuanas were admired for their flamboyant style of dress, and it was not uncommon for them to run local markets; they were autonomous and matriarchal. [1] Later social figures, most notably Frida Kahlo, adopted this fashion in response to the political climate of her time; the Tehuanas rose as a cultural symbol. Kahlo took this fashion and mixed and matched it with traditional dresses from other places. Kahlo’s loose ties to Indigeneity beckon an exploration of how Indigenous historical actors were selectively praised by more visible cultural figures for their influence. It is telling that when people see this image, they will likely think of Kahlo before the Zapotec People of Tehuantepec. Do you?

[1] Sayer, Chloë. “Traditional Mexican Dress · V&A.” Victoria and Albert Museum, 2018. https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/traditional-mexican-dress.