Networks of Independence

Reconstructing how information spread amongst a complex collection of insulated yet connected social networks helps us better understand how the Spanish Atlantic Monarchy fell apart by the 1820s. By the first decade of the 19th century, New Spain (colonial Mexico), was crisscrossed by several social and political networks, including networks of elites; networks of the general population; networks of men and networks of women; religious networks and academic networks—all of which overlapped to some extent. This group of objects exemplifies how distinct yet connected groups of people operated to spread information and facilitate the questioning of sovereignty and loyalty in late colonial Mexico.

Contributors:

Christian E. Lumley, Brett Gaudet, Brandi Foster, and Diana Guizado

Behold, a glimpse of Mexico from 200 years ago

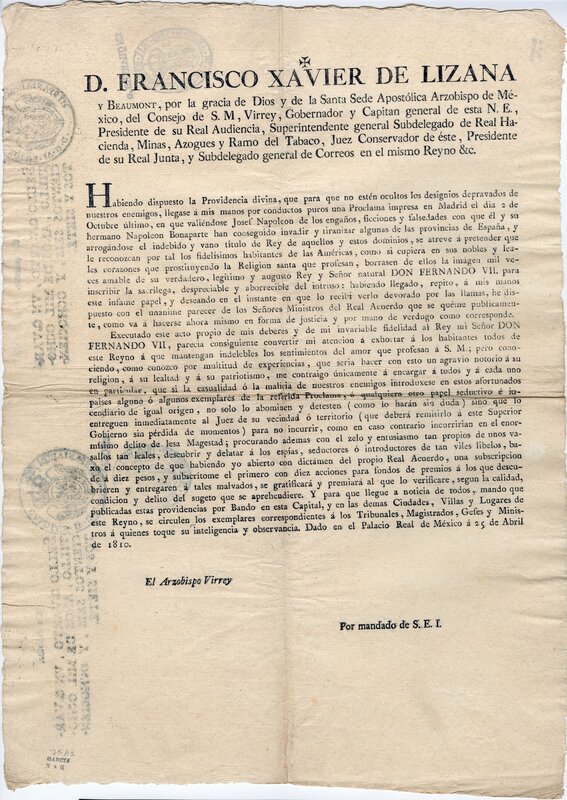

An unmistakable symbol of the Catholic faith, a Maltese cross, can be seen at the top center of the nearly pristine document. Printed in April of 1810, presumably by a secretary for the Palacio Real and the Viceroy of the Archdiocese of Mexico, this proclamation served both to urge the continued loyalty of the people of Mexico to Fernando VII in light of his contemporary exile by Napoleonic forces and to condemn Napoleon’s claims to the region. More broadly, the document highlights the necessary influence of the Catholic Church in maintaining monarchical ideals and securing the legitimacy of Fernando VII.

First-hand Account of Guanajuato about the Insurrection of Cura Hidalgo and the taking of the Alhóndiga de Granaditas

This handwritten document, penned by Juan José García Castrillo in December of 1810, provides a first-hand account of the insurrection of Cura Hidalgo and the taking of the Alhóndiga de Granaditas in Guanajuato City, Mexico during the Mexican War of Independence in September of 1810. The document was disseminated throughout the Mexican state of Guanajuato in December of 1810. García Castrillo writes a military battalion with a negative view of Hidalgo and his actions, and also describes the presence of the Indian population, which he finds particularly concerning. This manuscript aids in highlighting the importance of the role that religion and religious networks played in Latin America, and the influence that religious officials such as Cura Hidalgo had during this time.

Silent Lioness - January 27th 1810

Leona Vicario, an affluent woman who lived in central New Spain, had an intimate group of connections, one of them was her friend Pilarito to whom she writes this letter - these connections allowed her to become a heroine in the war for Independence. Before Miguel Hidalgo uttered the “Cry of Dolores”, the European Enlightenment had a great impact in people’s thoughts about the world and New Spain, particularly in creole women like Leona Vicario, who used her knowledge to awaken women like Pilarito and later to aid the insurgents.

Vicario was a strong writer who spoke fearlessly about her beliefs- a privilege that many women didn’t have. Leona’s letter to Pilarito allows us to ask: what were the networks women with different status had? Did the hierarchy of these networks shaped women’s participation and recognition in Independence? The latter could be true because of the many narratives of patriotic lower class and indigenous women that, unlike Leona’s, weren’t preserved to study.

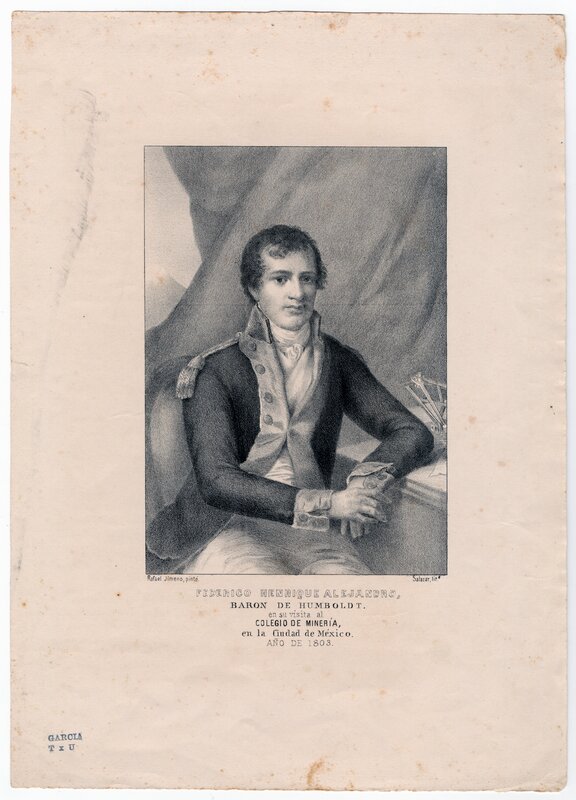

Painting of Alexander von Humboldt by the Spanish painter Rafael Jimeno

This handbill, which features a black and white lithograph copy of a painting of Alexander von Humboldt by the Spanish painter Rafael Jimeno y Planes, was made to promote Baron von Humboldt’s visit to the Colegio de Minería in Mexico City in 1803. Established in 1792, the college became one of the most important academic institutions in Mexico. It was the first institution in New Spain to provide a strictly scientific education to its students. In short, this document shares an endorsement of a renowned European scientist and displays of a top scientific institution. Through these aspects, it provides a rare glimpse into the well-developed scientific culture of the Spanish Atlantic Monarchy, which in many cases has been denigrated or even purposefully excluded from a more general discussion of the European Enlightenment.