Invasion of Mexico

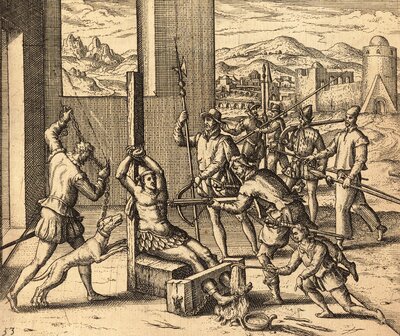

Illustration of an Indigenous-European encounter drawn on amate paper by an unknown artist, circa sixteenth century.

1521 was a fateful year for Mesoamerica. In February, thousands of Tlaxcalteca and Texcoca warriors joined European invaders to besiege and occupy Tlacopan and Texcoco—two of the Nahua Triple Alliance city-states. From these strongholds, the rebelling Indigenous groups and the conquistadors attacked Tenochtitlán between May and July. In August, they captured Cuauhtémoc, the last tlatoani (ruler) of Tenochtitlan, and toppled the Aztec Empire. This violent confrontation gave birth to New Spain.

However, the Indigenous-European negotiation that took place years prior was key. The events that led to this revolution paint an incredibly complex picture of splintering and consolidating alliances. As the European invaders and their language interpreters made their way towards the Valley of Mexico in 1519-1520, they established critical agreements with powerful Indigenous groups. These included the Tlaxcalteca and Totonac, independent city-states who had repelled Aztec domination, and disenchanted Texcoca factions. While the conquistadors provided the pretext to challenge the Nahua Triple Alliance, these Indigenous communities collectively sealed the fate of the Aztec Empire.

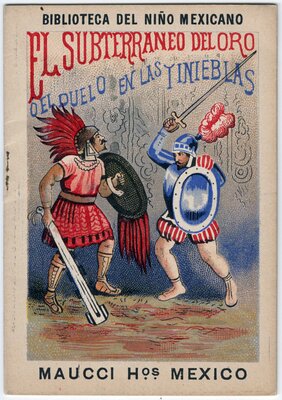

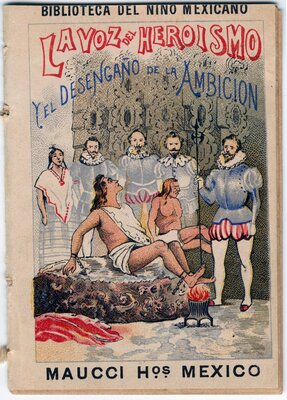

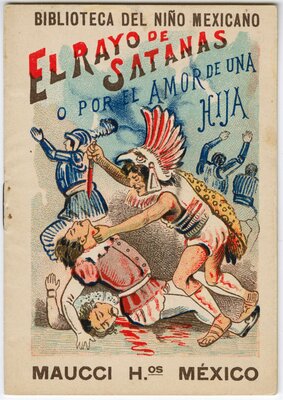

The Benson Latin American Collection preserves a rare Indigenous perspective of the events that led to the downfall of the Aztec Empire—the lienzo (canvas) of Tlaxcala. The item illustrates the 1519 meeting between Xicoténcatl I, the Tlaxcalteca political head, and Hernán Cortés—enabled by the language interpretation of Malintzin, an Indigenous woman—that resulted in the most decisive of these Indigenous-European alliances. It comprises two folios of a larger, now-lost codex the Indigenous Republic of Tlaxcala sent to the Spanish Crown after the conquest in which they requested an exemption from tribute considering the military aid they had offered the conquistadors.

Conquistadors

Through the centuries, the recounting of the conquest has centered on Hernán Cortés. He was the Spaniard who led the unsanctioned expedition into mainland Mexico, formally claiming land for Spain to later justify his actions. While he instigated the invasion, he was only one out of many agents who contributed to the overthrow of the Nahua Triple Alliance from power. Among these were the conquistadors that accompanied him.

These men were mostly feudal lords led by self-interest. Generally identified as “White Spaniards,” they did not necessarily consider themselves as such—they were Castilian, Galician, or Flemish, among other regional European identities, and at least one was of African descent. Although history has often painted them as being exceptional in their colonization approach, these conquistadors were simply deploying practices developed since the early 1400s.

Indigenous Allies

Autonomous and rebelling Indigenous groups, coupled with European diseases, overcame the Nahua Triple Alliance, not European technological & cultural ‘superiority’. The Tlaxcalteca confederacy, comprising the city-states of Tepeticpac, Ocotelolco, Tizatlán, and Quiahuiztlan, was perhaps the strongest supporter of the European invasion. They, like other Indigenous communities that had historically fended off the subjugation of the Aztec, were not naïve to the intentions of the conquerors. They took the opportunity the Europeans presented to further their local interests.

In 1519, the tlatoani of the Tizatlán city-state—Xicoténcatl I—allied the Tlaxcalteca with Cortés’ affront, which already included the Totonacs from Cempoala. Although his son and leader of the warriors—Xicoténcatl II—opposed the alliance, the elder sided with the tlatoani of Ocotelolco—Maxixcatzin—who favored it. Unwillingly, his son led ten thousand Tlaxcaltecas into Tenochtitlán in 1521.

Women

Malintzin, also known as La Malinche or Doña Marina, was critical in the establishment of these alliances. Enslaved, Chontal Maya rulers gifted her to Cortés at a young age in 1519. Accounts noted her diplomatic & linguistic skills in making allies out of enemies as his Nahuatl interpreter.

She exemplifies the importance of women as political and cultural bridges between Indigenous communities and the Europeans during the invasion of the Americas. For example, Tlaxcala’s rulers offered their daughters in marriage to cement their alliance with the conquistadors. They also gifted other Indigenous women as chattel to attend to Cortés and his men, much like the Maya had done with Malintzin in Potonchán earlier.

Bibliography

UT Catalog | Worldcat | HathiTrust | Díaz del Castillo, Bernal. The True History of the Conquest of Mexico. London: Printed for J. Wright, by J. Dean, 1800.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Restall, Matthew. Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Townsend, Camilla. Malintzin’s Choices: an Indian Woman in the Conquest of Mexico. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2006.

Additional Resources

Malintzin: Indigenous Women Discover Spain (World History Lesson Plan)