Indigenous Worldviews

Painting of the Mixtec town of Amoltepec, Nahua for “hill of the soap plant”, by an unidentified Indigenous artist, 1580. A partial circle of nineteen logographs (symbols) representing individual city-states and a river delineate the perceived boundary of the community. Within are the Indigenous ruler’s palace, the local Catholic church, and subordinate towns.

Indigenous people were not homogenous before nor after the European invasion of the Americas. The Aztec Empire, headed by the Triple Alliance of the Tenochtitlán, Texcoco, and Tlacopan city-states, comprised countless ethnic communities. A shared language—Nahua—and the movement of ideas, people, and goods it facilitated principally made the Alliance's sphere of influence and domination into an empire.

Community Organization & Identity

Subjugated ethnic states had their own regional language and distinct cultural and political dynamics. Each altepetl, a Nahua compound of the words “water" (alt) and "hill” (tepetl), was "fiercely individualistic" and considered itself "a radically separate people"—"a whole, not a small piece of a larger whole" (Mundy, 105). As a microcosm of the broader Aztec Empire, these city-states also ruled over and extracted tribute from calpolli (subunits) that had their own identity and leaders.

This map of Misquiahuala and Atengo (1579) depicts this individualism. The unidentified Indigenous artist depicted the perceived boundaries of this region with neighboring altepetls. The painter represented each bordering city-state with a symbol, typically in the form of a stylized hill, along the edges of this painted hide. The logograph of Misquiahuala, which means “place of mesquite circles” in Nahua, dominates on the center-left of the composition. Desert plants typical of the local environment beautifully illustrate the tepetl design.

Beliefs and Rituals

As the Triple Alliance brought altepetls into the imperial fold, they also incorporated local gods into the Nahua pantheon. The principle of duality, or opposites, structured this supernatural world, which the Nahua believed determined creation and destruction in the earthly realm. Many of these gods embodied the natural elements—earth, wind, water, fire—vegetation, and the concepts of birth, fate, and death. Given their awesome power, Aztec kings made ritual offerings and sacrifices to the gods to ensure prosperity.

Half a century after the conquest, Franciscan Fr. Jerónimo de Mendieta depicted in Historia Eclesiástica Indiana (circa 1571) what he understood to be common elements of religious ceremonies that took place at the Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan. Although it depended on the god, Aztec leaders would most often sacrifice enslaved or captive men, women, and children atop the structure. For them, the shed blood was a non-renewable resource that fertilized and regenerated life. The sacrificed would then be hurled down the steps (as seen on the portrayed pyramid's right side) and flayed, or have their skin removed. Wearing the hide, Aztec priests and kings would conclude the rites with dances at the base of the temple (noted as "saltatio indorum" in the drawing).

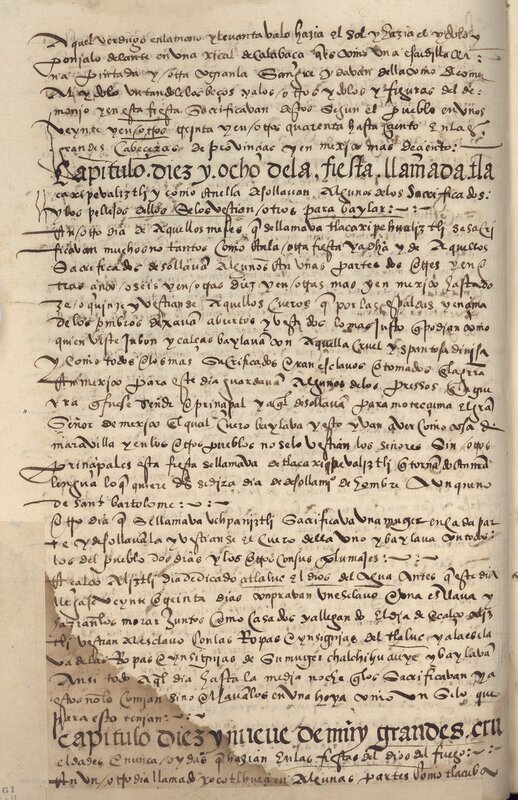

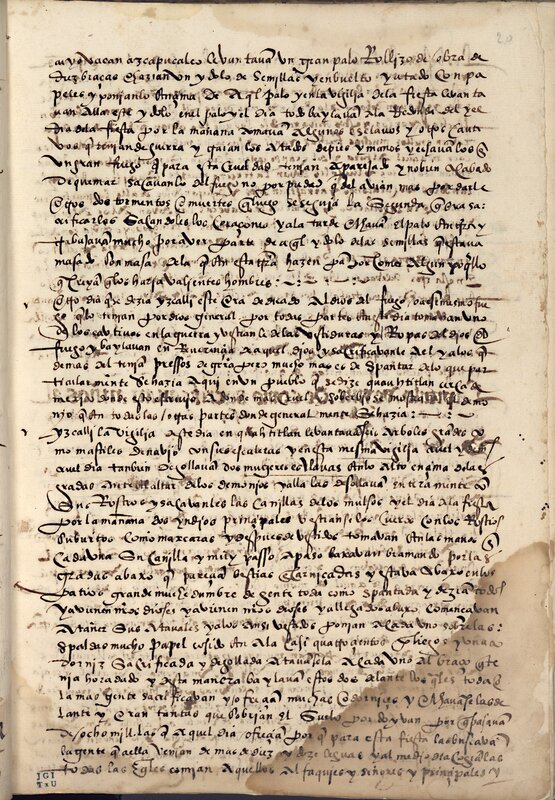

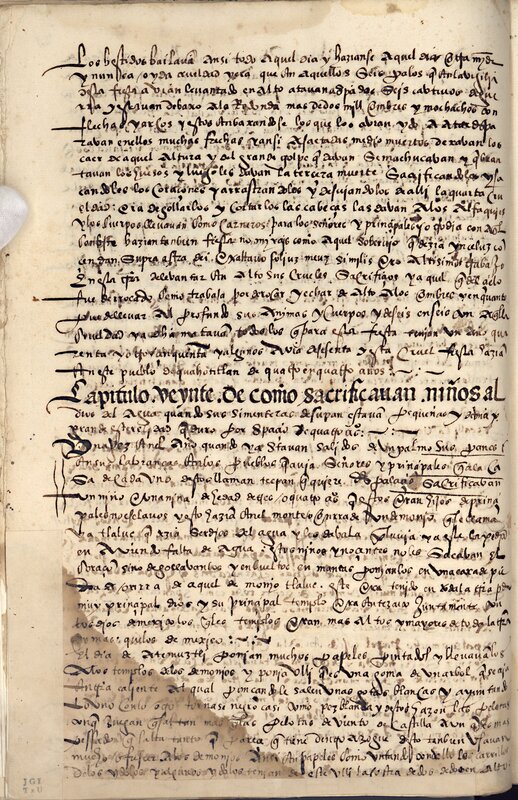

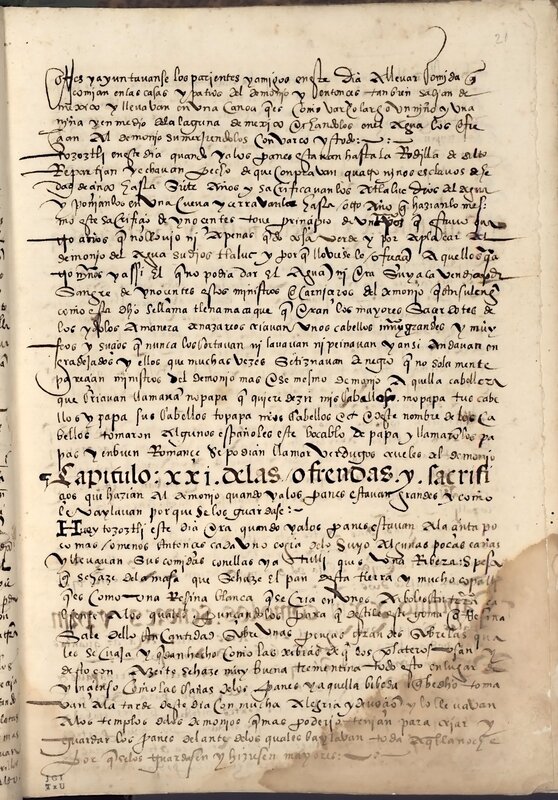

Another Franciscan missionary, Fr. Toribio Motolinía, wrote about some of these rituals in "Libro de Oro" (circa 1541-1549). In the pages below, he described the Tlacaxipehualiztli ("Flaying of Men"), Huey Tecuilhuitl ("Great Feast of the Lords"), and Teotleco ("Arrival of the Dieties") ceremonies, among several others. Most of these rituals entailed the human sacrifice and dances as Fr. Mendieta illustrated.

- "Chapter eighteen of the festival called tlacaxipehualiztli"

- "Chapter nineteen of very great and never heard cruelties that they did in the festivals of the fire god"

- "Chapter twenty of how children were sacrificed to the god of water"

- "Chapter xxi of the offerings and sacrifices that were made to the devil"

- "Chapter xxii of the feast and sacrifices made by the merchants"

Nahua Calendar

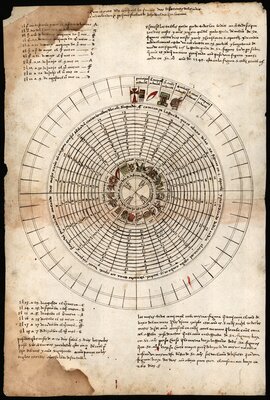

These ceremonies occurred on specific dates. The Aztec followed a 260-day ritual calendar that consisted of thirteen days per "week" and twenty "weeks" per year. This system interlocked with a 365-day agricultural calendar that comprised twenty days per "month" and eighteen "months" with five extra days per year. Since most of these gods and their ceremonies determined agricultural growth in Indigenous worldviews, this latter calendar coincided with the seasons.

In 1549, Fr. Toribio Motolinía created this diagram to cross-reference the Nahua calendars with the Julian calendar. The text on the left translates the Nahua "months" with Western dates. The wheel diagram charts the intertwined cycles of days and months in relation to the four main Nahua years: Reed (year 1), Flint Knife (year 2), House (year 3), and Rabbit (year 4).

Tribute

The agricultural production these calendars governed not only sustained the altepetls, but also the Aztec Empire. City-states subject to the Triple Alliance had to give tribute, an offering comparable to a tax. This was typically in the form of crops, textiles, feathers, jewelry, and even people.

Remnants of the pre-conquest tribute system across distinct ethnic states can be seen in this map of the Cempoala region (1580). The district comprised four altepetls, Cempoala, Tzaquala, Tecpilpan, and Tlaquilpa. Using red lines, the Indigenous artist demarcated the city-states' calpolli, which were fifteen in total, and depicted some of the tribute paid to the Aztec (portrayed just below the main church with a bell tower). The painter also identified the ethnicity of local rulers through their clothing: Those wearing brown hide cloaks represented Otomí rulers, while Nahua lords wore white cloaks and a headdress.

Bibliography

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Clendinnen, Inga. The Cost of Courage in Aztec Society: Essays on Mesoamerican Society and Culture. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Knight, Alan. Mexico: From the Beginning to the Spanish Conquest. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Lockhart, James. The Nahuas after the Conquest a Social and Cultural History of the Indians of Central Mexico, Sixteenth through Eighteenth Centuries. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1992.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Mundy, Barbara E. The Mapping of New Spain: Indigenous Cartography and the Maps of the Relaciones Geográficas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Townsend, Richard F. The Aztecs. London: Thames & Hudson, 2009.

Additional Resources

!["La orden y cuenta que antiguamente tenían [los Nahuas] para contar los años”, página 1](https://exhibits.lib.utexas.edu/images/1085/full/!400,400/0/default.jpg)