Northern Borderlands

"New Mexico and Florida" by N. Sanson d'Abbeville, 1656. The map depicts northern New Spain and French occupied areas in present-day southern and southwestern United States, demarcating the different kingdoms and territories.

European incursions into the region presently known as the American South and Southwest started years before the fall of Tenochtitlán in 1521. Nine years earlier, a series of Spanish expeditions sought to penetrate and conquer the Florida peninsula to no avail. It was not until the mid-sixteenth century when the Spanish Crown initiated a concerted effort to expand the novohispano territory and keep other colonizing world powers—most notably France—at bay.

Spanish exploitation and Indigenous revolt characterizes much of the northern frontier's colonial history. Driven by self-interest, Spaniards set their sights on the region soon after their conquest of central Mexico hoping to “discover” and extract resources. As with most imperial expansions, missionaries from the Franciscan, Dominican, and Jesuit religious orders accompanied the conquistadors to lead the "spiritual conquest". Although some Indigenous peoples established reciprocal alliances with the invaders, many continued to rebuff their advances throughout the "borderlands" well after the independence movements.

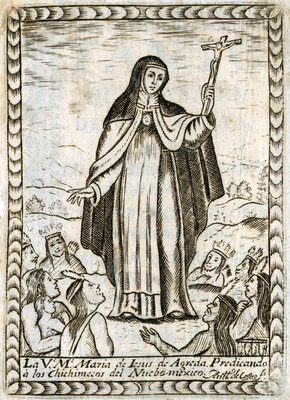

Depiction of a missionary in the Indigenous frontier by engraver Giovanni Girolamo Frezza (1659-1743), circa 1697.

Coahuila and Texas

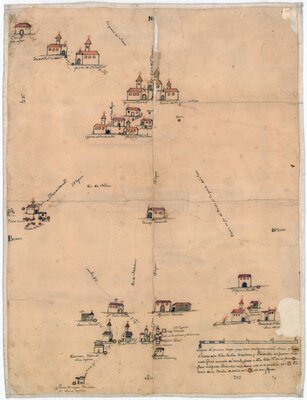

Mining prospects and cattle ranching drove Spaniards to the northeastern part of present-day Mexico in the 1550s. In this map of Coahuila, one can see the network of groupings of missions, Spanish towns, forts, haciendas, and ranches making up the area. Established to "pacify" the warring nomadic and semi-nomadic Indigenous groups of the area, Franciscan missions principally tapped into the ranching industry to sustain their operations.

Spanish conquistadors had also journeyed into Texas prior to the conquest of Mexico in 1519. However, the Crown did not set its conquering eyes on it until the French started colonizing near it in the second half of the seventeenth century. Threatened, royal officials hastily sent an expedition in 1689 to form a settlement, principally missions, along the Neches River in present-day East Texas. With the establishment of a spate of missions from 1716 until 1722 in that same area, the San Antonio River valley, and along the Texas gulf coast, Franciscan missionaries, like Fr, Antonio Margil de Jesús, managed to bring Texas into the Spanish imperial fold.

New Mexico

The Spanish had already invaded Cibola and Gran Quivira (present-day New Mexico) in 1540. However, it was not until Juan de Oñate’s 1598 onslaught and establishment of Santa Fe that the Spanish Crown decidedly occupied the region. With the sword and the Cross, Spanish colonizers and Franciscan friars thereafter extracted labor and goods from the Pueblo communities. However, the Indigenous people did not readily concede. The Acomas revolted when Oñate invaded the region, and in retaliation, the conquistador massacred, enslaved, and mutilated them. Although this slaughter prompted his removal in 1607, subsequent Spanish officials continued the maltreatment and exploitation of the Pueblo people.

The Franciscan’s attempt to extirpate all aspects of Puebloan beliefs proved to be the last straw. In 1680, the surrounding Puebloan communities united under the leadership of Po’ Pay, a Tewa spiritual leader, and drove the Spanish and their Indigenous allies out of the region into El Paso. The Puebloans kept the Spanish away for twelve years, making Po’ Pay’s Rebellion the first successful expulsion of the Spanish in North America. After negotiating peace with the Pueblo communities, the Spanish crown reconquered northern New Mexico in 1692.

Sonora and Baja California

Drawn by the possibility of mineral wealth, colonizers also pushed into the Sonora and Baja California area in the early seventeenth century. As conquistadors sought to conquer and settle the area, Jesuit fathers led the indoctrination efforts through the establishment of missions. However, the continuous resistance of the Tepehuán, Pima, Seri, and many other Indigenous groups prevented the Spanish from establishing a formal and stable presence in the area.

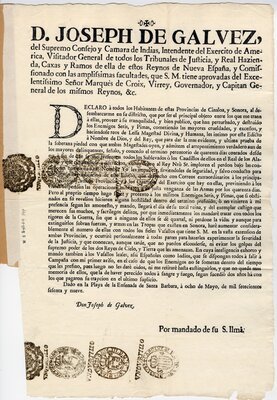

Even after a presumed "pacification", the Indigenous groups continued to rebel well into the eighteenth century. This printed map of the region includes vignettes in the bottom corners depicting Indigenous resistance to Jesuit acculturation efforts in 1734. The struggle continued thirty years later: In 1769, royal inspector José de Gálvez was granting forty days of amnesty for Seri and Pima if they surrendered to the Spanish army after a series of rebellions in the province. Otherwise, they would face the full force of the Spanish military.

"Inspection of the missions in Sonora and its contours" by cartographer Juan Antonio Baltasar (1697-1763), 1752. The map demarcates the Jesuit rectorates of San Francisco Xavier, San Francisco de Borja, and Santos Mártires.

The Franciscans were territorial of the northern frontier. They considered the present-day American Southwest—northeastern Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas—their spiritual domain, rebuffing any encroachment from other religious orders. Initially, the Bishop of Durango ordered the Franciscans to make inroads into Arizona. Dissatisfied with their progress, the prelate asked Philip V in 1716 to send Jesuits from California. Expectedly, the Franciscans objected, referencing established law prohibiting “missionaries of one order from interfering in the missions of another.” Claiming that the territory had already been “watered with the blood of their missionaries,” the Franciscan’s attorney general formally requested that the Moqui, or Hopi, region remain part of their frontier province.

Bibliography

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Chipman, Donald E. Spanish Texas, 1519-1821. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1992.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Deeds, Susan M. Defiance and Deference in Mexico’s Colonial North Indians Under Spanish Rule in Nueva Vizcaya. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2003.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Jackson, Robert H. New Views of Borderlands History. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1998.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Mann, Kristin Dutcher. The Power of Song : Music and Dance in the Mission Communities of Northern New Spain, 1590-1810. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2010.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Rubio Mañé, J. Ignacio. El virreinato. México: Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas, UNAM, 1983.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Sandos, James A. Converting California : Indians and Franciscans in the Missions. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004.

UT Catalog | Worldcat | Wade, Maria de Fátima. Missions, Missionaries, and Native Americans: Long-Term Processes and Daily Practices. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2008.

UTEP Archival Collection: Ysleta Mission baptismal records translations, 1792-1803