Craftwork

Late twentieth-century free-market capitalism has encouraged mass production. To meet the market demands of the Global North, goods are often manufactured in the Global South for a lesser price in exploitative work conditions, as illustrated in the photograph of the textile factory from the Landon Rupert Chambers Photograph Collection. As a result, products move easily across transnational borders while people, in search of better opportunities, are restricted in their migratory patterns.

The items in this section celebrate work done with the hands. As Ruth Phillips points out, “sewing, beading, and embroidery became important ways of ensuring the continued vitality of visual cultures that might otherwise have disappeared” (1998: 198). Craftwork is a vehicle for maintaining local aspects of identity, demonstrating the resiliency and perseverance of a culture. Recent research has linked craftwork to various types of healing and reconciliation. For example, not only has it played a role on a macro level with Indigenous communities in Canada finally sharing their stories to the Truth and Reconciliation Committee through the Living Healing Quilt Project, but it has proven useful for individuals working through PTSD and anxiety.

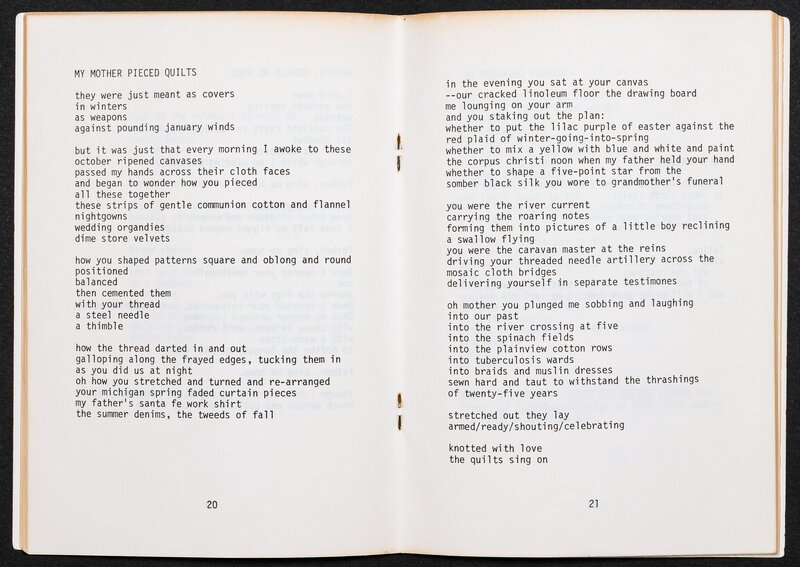

Teresa Palomo Acosta’s “My Mother Pieced Quilts” (1976) reflects on a mother-daughter relationship told through the handmade quilts that a mother used to cover her daughter on chilly winter nights. With each patch comes a memory, extending quilting from practical task to one that binds family.

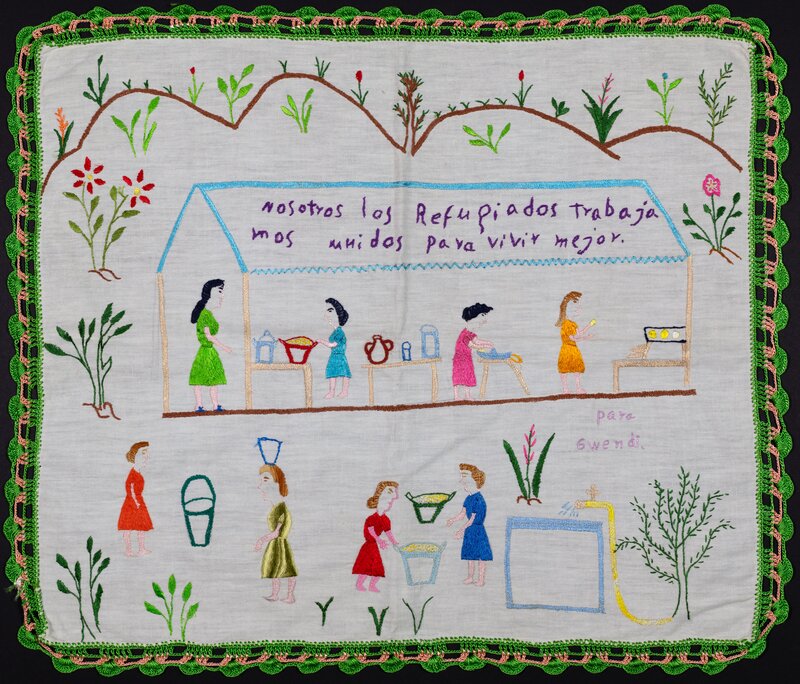

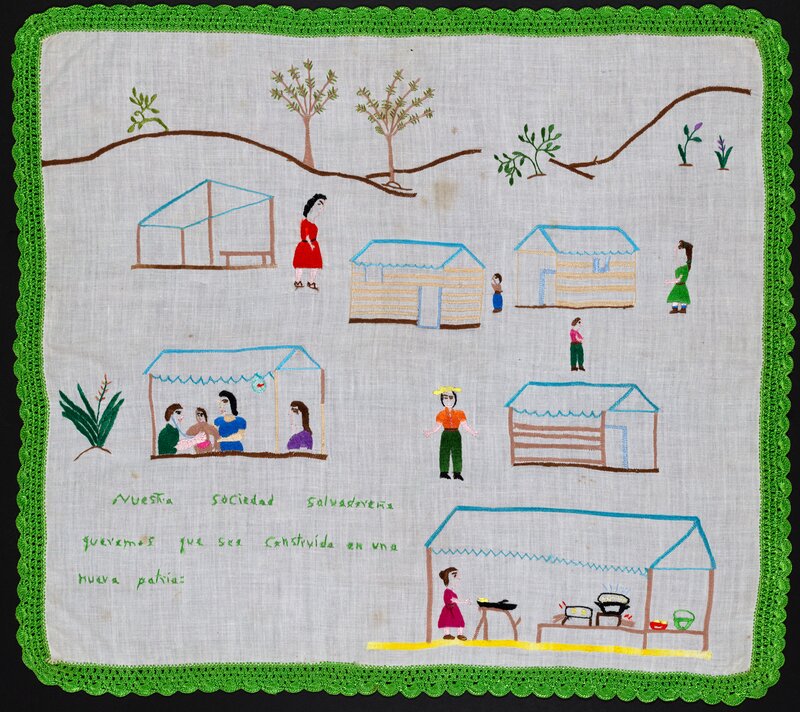

Moreover, the embroidery work found in the 1980s Colección Bordadoras de Memorias of post-custodial partner Museo de la Palabra y la Imagen (MUPI, El Salvador) uses handcrafted materials to tell the stories of human rights violations. Stitched by women for the United Nations to recount their life in refugee camps, these stories reimagine better societies founded on equity and justice. Envisioning a world without the violence and violations that set them on a path toward political asylum puts them one step closer to achieving it.

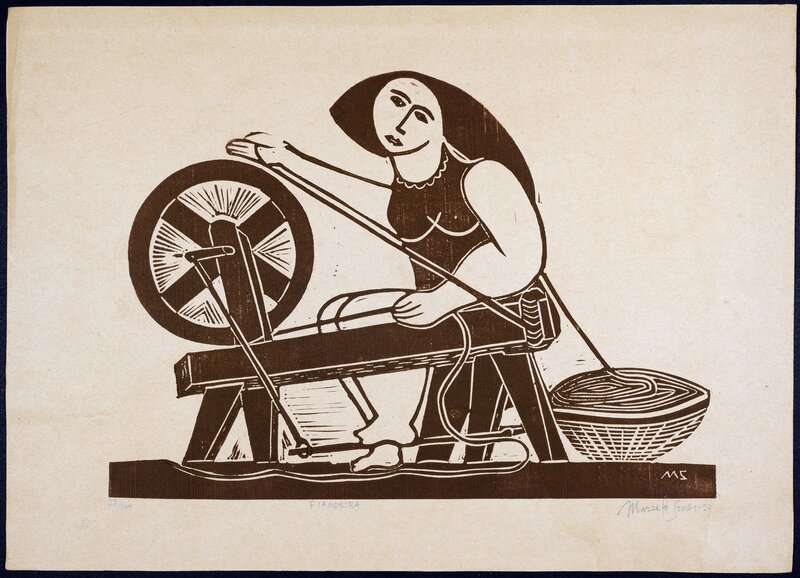

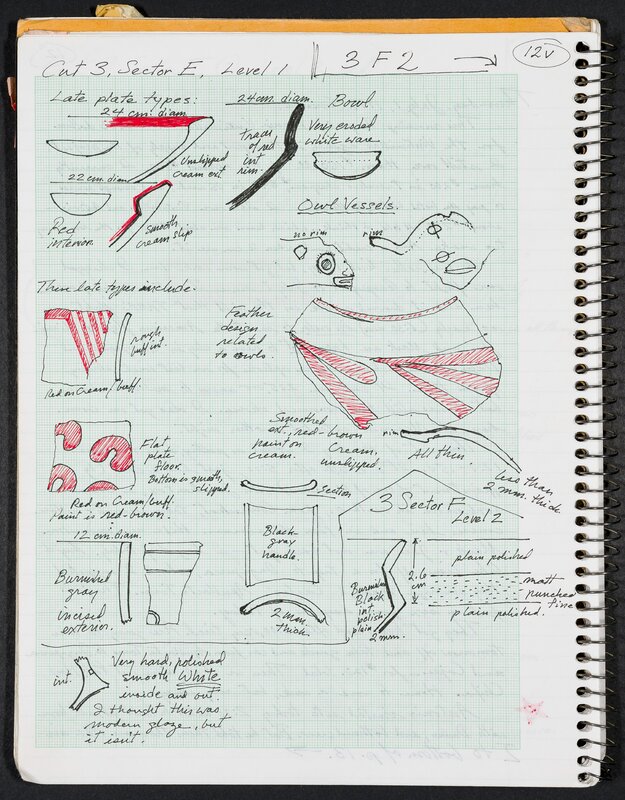

Marcelo Soares’s Fiandeira (undated) provides a visual of a similar type of craft work, while Terence Grieder’s undated archaeological illustrations turn our attention to pottery work as a distinctive marker for style across different indigenous societies.