Community Stories and Songs

This section consists of the stories and songs that strengthen a community and endow it with a sense of querencia, which Juan Estevan Arrellano defines as “that which gives us a sense of place, and that which anchors us to the land, that which makes us a unique people, for it implies a deeply rooted knowledge of place, and for that reason we respect it as our home” (2014: 50). Querencia can have different meanings for different groups. Indigenous communities have a connection to land that other groups can never fully understand. Similarly, in places like the U.S. Southwest, Hispanic and Latino communities, some of which have been there for centuries, have a querencia that is challenged by the relatively recent arrival of White European settlers. Still other communities understand this connection differently due to enslavement, political asylum, or economic opportunity that have forced them to engage with a previous homeland, figurative or literal, alongside a new sense of place.

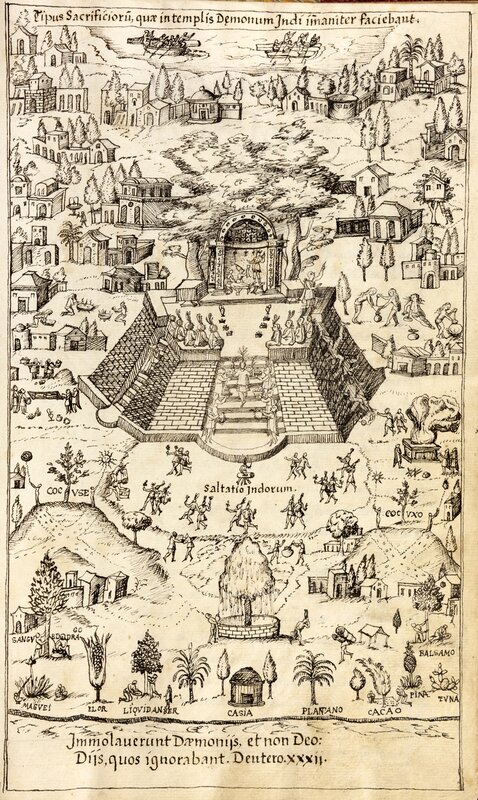

Originally written in 1571, Fray Jerónimo de Mendieta’s La historia eclesiastica indiana details an early account of Europeans trying to make sense of the spiritual knowledge possessed by Indigenous groups. Quick to violently denounce Indigenous beliefs as heresy, these accounts provide us with insight, however skewed and fragmented, into the markers that constructed a community.

The circular genealogy of Nezahualcoyotl (ca. 1580) suggests a shifting sense of belonging. As a type of land claim in colonial Mexico, the genealogy tells the story of multiple generations of a family whose ancestors were original, elite inhabitants of the area. The transition is present in the increasing number of Spanish names in the genealogy, revealing the colonial model of evangelization. It is a story of mestizaje, a phenomenon that the Mexican government has long promoted. Yet it often overlooks the darker reality that to be “mestizo” is to leave behind one’s Indigenous roots.

Catalina Delgado-Trunk’s Camino al Mictlán (ca. 2018) returns to those roots by pointing to the journey to the nine levels of the Aztec underworld. This is where Aztecs would go upon death, and the journey necessitated a dog companion to guide the soul past devastating winds that blew knives and ferocious jaguars, among other challenges. Camino al Mictlán is an integral part of the Aztec cosmovision and, therefore, a binding aspect of the culture.

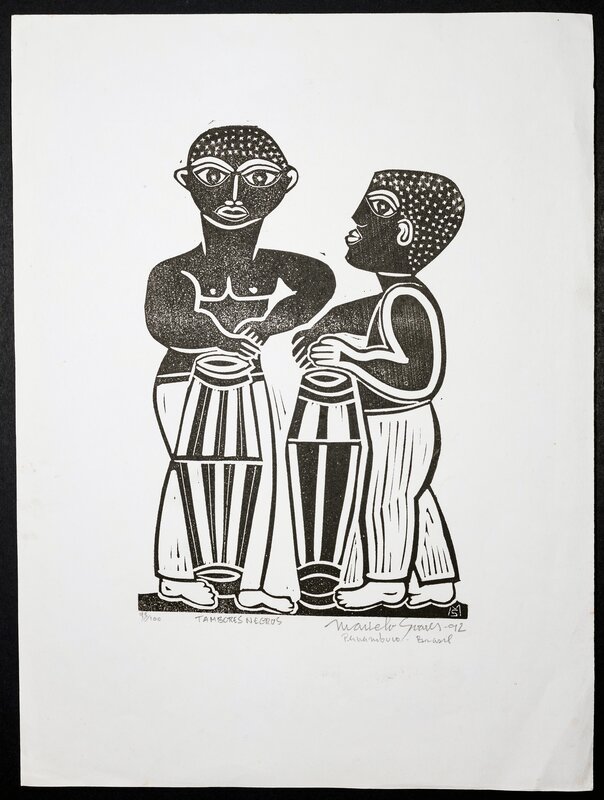

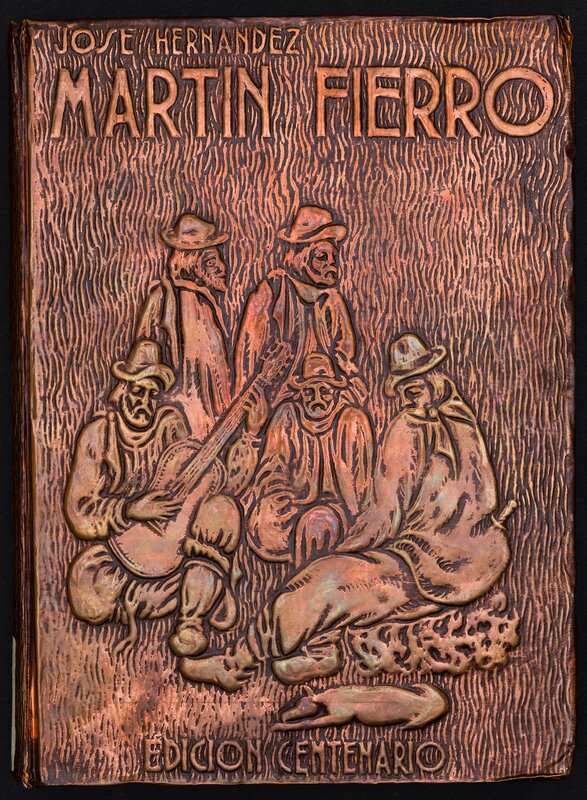

Cultures are bound by the stories they tell. Whether gathered around a fire with a guitar as in an illustration of Martin Fierro, or the African drums in Marcelo Soares’s woodcut, communities come together to share their stories and songs. In Nicolás Patricio Vigueras’s Tepehua and Spanish tale “Pedro y la acamaya” (2000) and PCN’s “Hay un mundo donde lo que no se ve, ¡existe!” (1978), communities share stories, often with a magical realist flair, to explain local happenings.

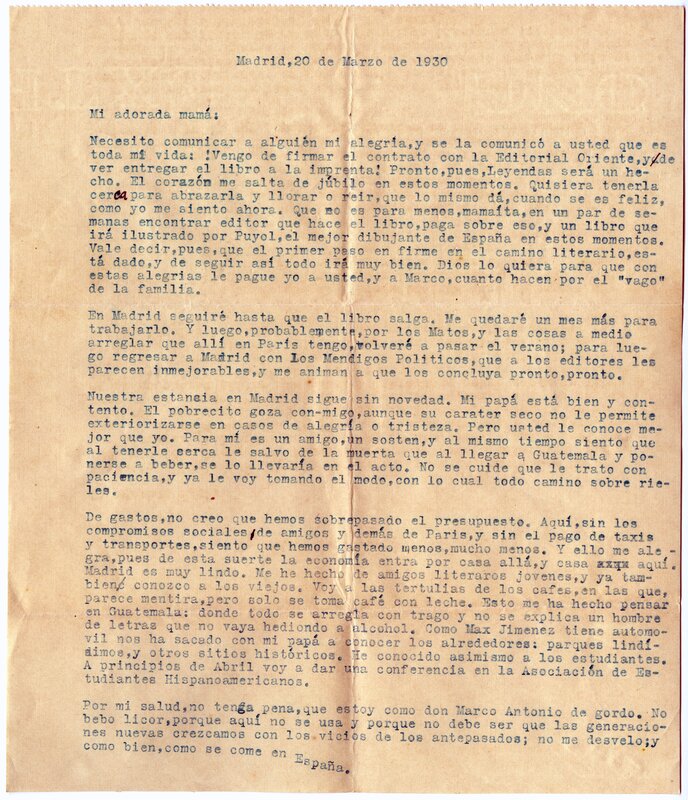

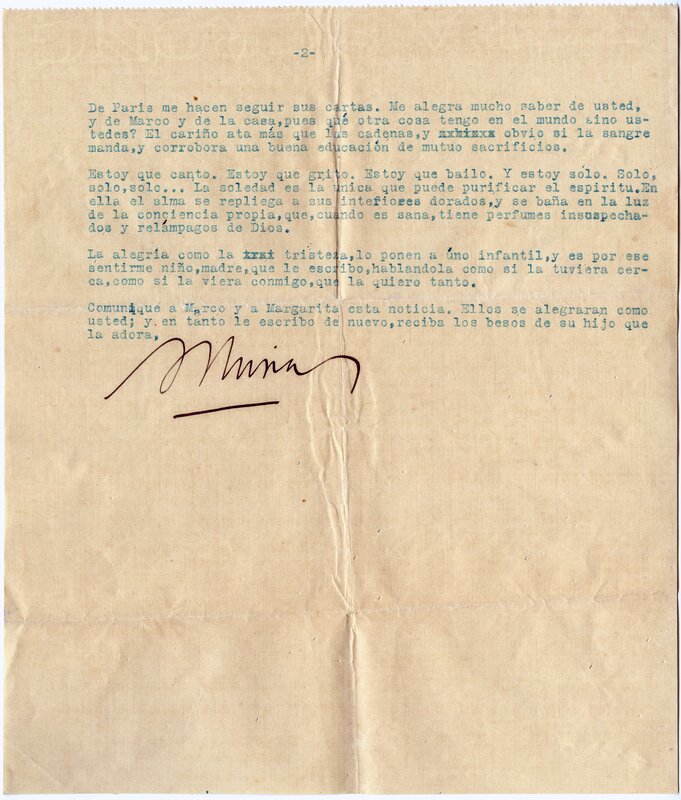

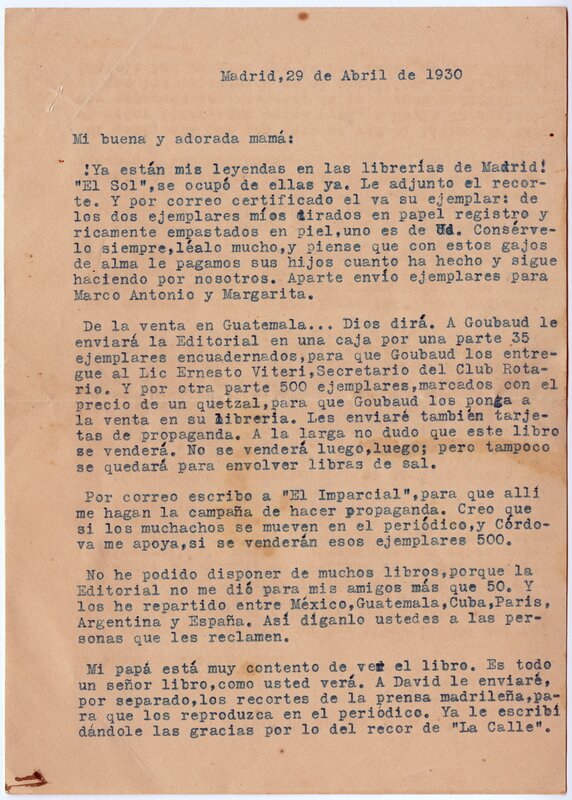

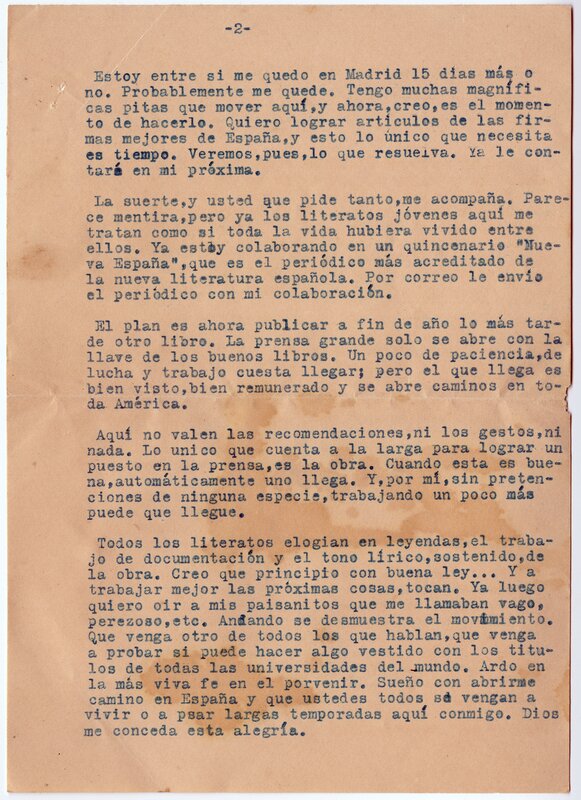

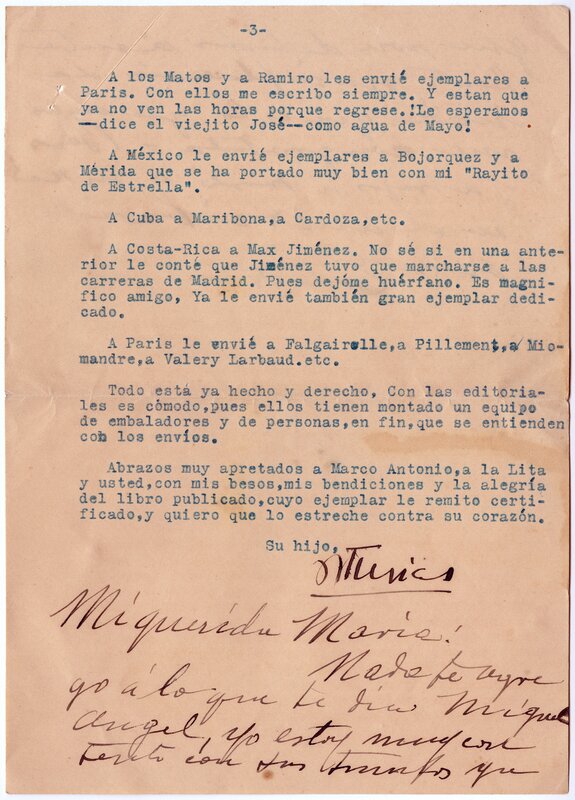

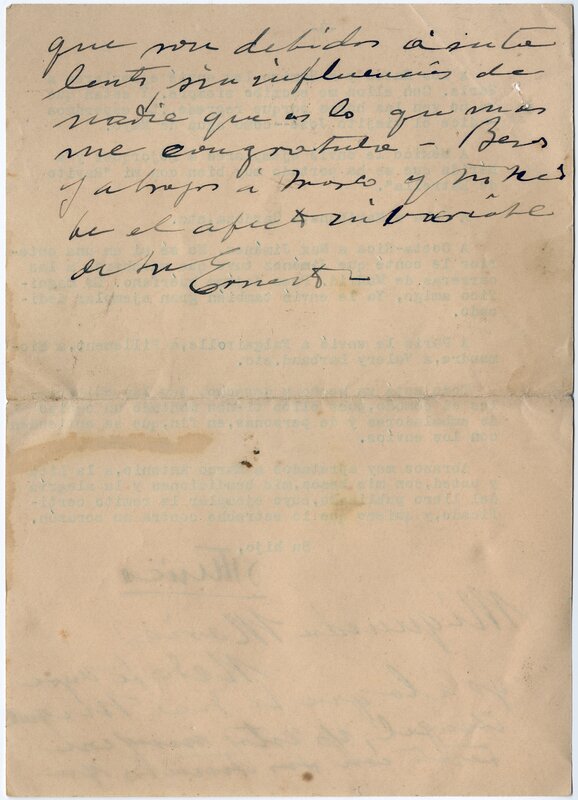

In Miguel Ángel Asturias’s letters to his mother, the author expresses the glee and triumph of publishing his first book, Leyendas de Guatemala (1930). Written in France, Asturias’s stories not only garnered more attention for Guatemala and the narratives of Indigenous groups in the country, but also gave Asturias a sense of belonging to his native country in moments of intense homesickness.

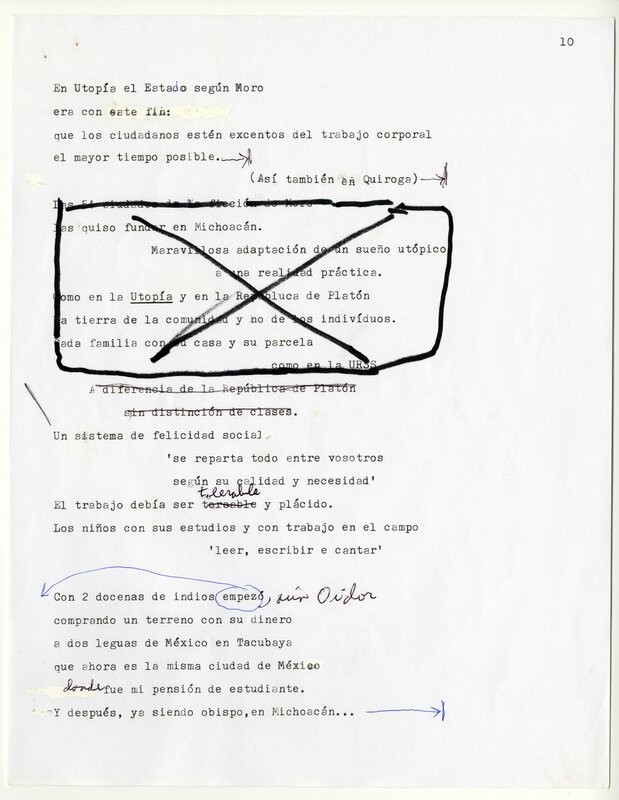

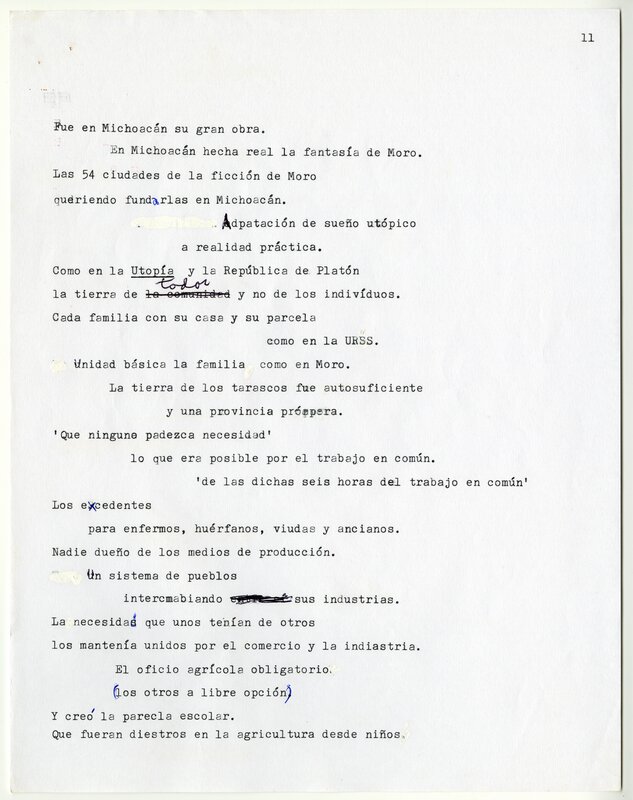

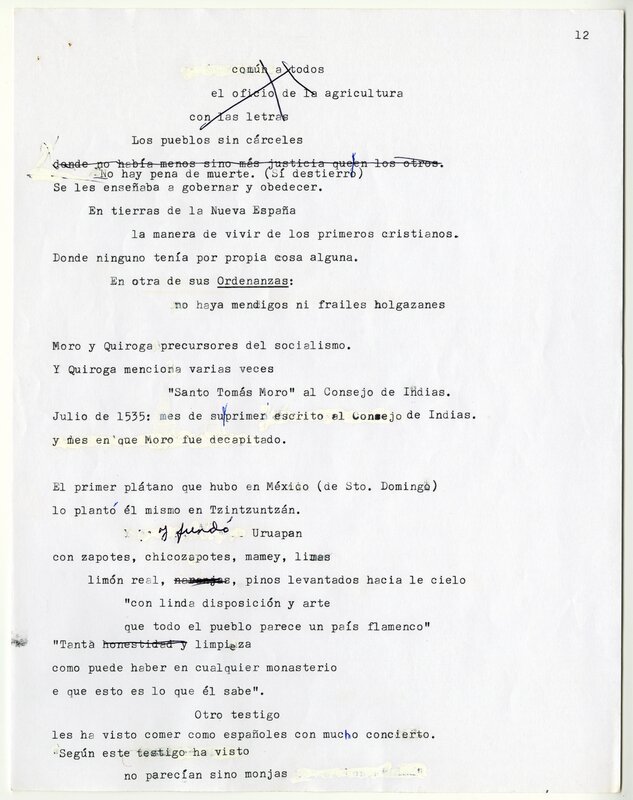

A fragment of Ernesto Cardenal’s “Tata Vasco” (undated) concludes this exhibition by reflecting on a utopian society established by Vasco de Quiroga in sixteenth-century Michoacán and the hope for a future utopia where different forms of knowledge inform each other.