Hooking

Hooking is a navigational strategy which guides the listener or reader toward a predetermined destination that is advantageous for the speaker. It is a “way to maintain control,” by “‘dangling a hook’ that will lead to the next question” (GLAAD n.d., 25) Hooking “steers” the audience through sound bites and flagging to gain control of a conversation and, then, to communicate another important message. The strategy draws in a particular listener or reader through the use of rhetorical questions and inciting remarks to cultivate attention to an effort or cause. US Latine activists employ hooking in multiple media as a way to engage specific audiences, move to new sound bites and flagging opportunities, and maintain a steady voice throughout their respective efforts.

US Latine labor activists utilize hooking in broadcast media by emphasizing sound bites and flagging. Onda Latina’s “Chicano Farm Worker’s Struggle” and “Chicanas In The Labor Market” audio employ hooking by flagging a sound bite at the very beginning of the recordings. This allows for the interviewees to speak in more detail on certain subjects and steer the conversation in ways which support their goals. For instance, the former recording, “Chicano Farm Worker’s Struggle," includes the following statement:

This comment happens later in the interview, but, in the recording, it is positioned at the beginning to “hook” the listener and prompt the speaker to develop this claim.(3) The meaning of this message, then, guides the listener throughout the remainder of the recording. Similarly, but in print media, DROP OUT’s zine, featuring mail-in contributions, includes an article beginning with “I was one of the smart kids…” in bold, at the top of the submission (DROP OUT Zine n.d.). With this at the beginning, the following text is read knowing that the contributor is speaking as a, presumably, “other-than-smart kid.” Both instances exhibit hooking through leading statements encompassing sound bites and flagging, which promote the communication of US Latine activists supporting different movements. Hooking is a media communication strategy which promotes further engagement with movements’ messages to advance goals among US Latine activists.

In MariLes—Maricones and Lesbians—the journal’s introductory paragraph utilizes hooking via two rhetorical questions, both of which are answered in the line which follows. “I am a faggot, so what? I am a lesbian, so what?,” the October 1980 issue states, “the ‘so what’ of being lesbian/gay will be one of the many issues that we will be dealing with in this and future editions of MARILES” (MariLes Journal Vol. 1 Issue 1 1989). Here, hooking communicates the purpose of the journal and this specific issue by answering their own “dangling hook.” Similarly, another US Latine LGBTQ+ journal issue, “Food & Fetish” by Viva Arts Quarterly, utilizes hooking through suggestive imagery on the cover of their Summer 1993 issue. The grapes being licked by an unknown person's tongue draws in readers through ambiguity and innuendo to promote engagement with the inner content of the journal. US Latine activists utilize hooking to further the messages and efforts of LGBTQ+ movements to “defang the words and prevent them from doing us harm” (MariLes Journal Vol. 1 Issue 1 1989).

Hooking is present in early issues of journals such as Micro-Impacto: An HIV Education-Prevention Newsheet from CURAS, found in the LLEGO collection. Near the middle of the second column is the following statement: “You would think everyone would know by now that not following safe sex guidelines is a sure fire way to become infected. You would think everyone who is sexually active or about to would know about HIV and how not to acquire it. You would think that once you’ve started practicing safe sex you would be so relieved that reverting would be out of the question” (CURAS 1992; added emphasis). Repeated use of the phrase “you would think” functions to highlight the incorrect suppositions regarding HIV/AIDS. US Latine activists also utilize aesthetic repetition to “hook” audiences. This is seen in the “March Demands” document from March on Austin. Placement and bolding of the demands at the beginning of each paragraph communicate a “call to action” which is followed by further contextualization and information. Interestingly, the “reproductive freedom” and “an end to racism” hooks are circled by an unknown source, which can be seen near the bottom of the document (March Demands n.d.).

In US Latine labor movements, verbal forms of hooking are present in news broadcast and print media. This is seen in an interaction between Sister Pascal (of Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church) and Sheriff Corres (of Willacy County, Texas) in the UT Daily Texan newspaper clipping “Valley of Tears” in the Texas Farm Workers Union collection. Referring to Texas farmworkers walking off fields in protest, Pascal is quoted as saying “I don’t think they are lawbreakers. I think that everybody had a right to just wages… I feel that there were almost as many officers in the field as there were strikers. This was the Easter weekend, when people all over the highways needed protection… and here they all (officers) were” (Valley of Tears Newspaper Clipping n.d.). “Hooked,” Sheriff Corres responds, “she (Pascal) doesn’t know a god-damn thing about law enforcement. She has no god-damn business (dealing with) striking or non-striking people” (Valley of Tears Newspaper Clipping n.d.). Pascal undermines the credibility of Corres as a form of hooking to prompt Corres to react and exhibit law enforcement’s biased and violent responses to US Latine labor activists.

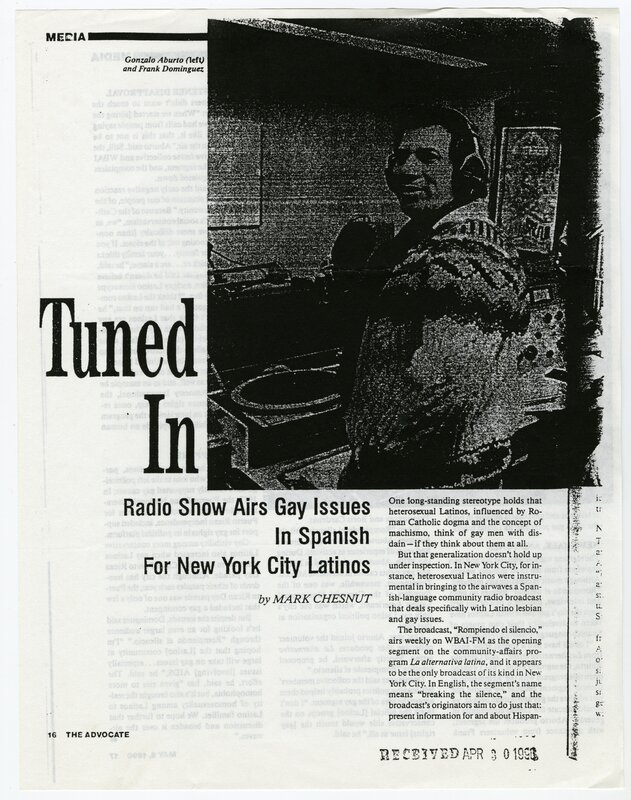

Otherwise, in another media article entitled “‘Tuned In’ Radio Show Airs Gay Issues in Spanish for New York City Latinos,” an interviewee, Frank Dominguez, verbally states “I don’t think the official [Latino] groups on the conservative side would touch the [gay rights] issue at all” (Chesnut 1990). This is because, according to Greene, who is in conversation with Espin, Hidalgo, and Morales, “it is the overt acknowledgement and disclosure of a gay or lesbian identity that is likely to meet with intense disapproval in Latino communities” (Greene 1994). Dominguez’s inciting remark draws attention to this disapproval and opens up room for engagement with how this influences the rights of Latine LGBTQ+ communities. This version of hooking develops a chance for Dominguez himself to respond to homophobia and Latino/a support in the following subsection, enforcing his message to readers. Dominguez says, under “Latino Support,” “I’m hoping that the [Latino] community at large will talk of gay issues,” and that this issue and others can be further disseminated throughout the media (Chesnut 1990). In this case, hooking is employed to speak in more detail about gay rights for US Latine peoples, and then it is furthered by calling for larger audiences to take up this same effort in future contexts.

(3) The use of audio in “Sound Bites” and “Hooking” is different in the message being communicated. Hooking involves the use of sound bites to “hook” the listener; sound bites involve summative and explanatory information.