Flagging

Flagging, as a communication strategy, is to “raise a ‘red flag’ to indicate the importance of an individual facet of your message,” specifically a facet of a sound bite (GLAAD n.d., 25). Flagging allows for referential summarization of a material—be that verbal communication or text in print media—and its meaning. Therefore, flagging is the practice of referencing meaning to solidify the importance of any message. US Latine activists utilize flagging to highlight the most important elements in the messages of certain civil, labor, and LGBTQ+ movements. Such a technique facilitates meaningful connections by foregrounding the importance of communicative sound bites.

In broadcast media, such as Onda Latina, flagging is immediately present in three audio recordings: “Chicano Poetry, Chicano Organizing,” “Farm Workers and Unionization,” and “Interviews with Farm Workers in The Rio Grande Valley of Texas.” Interestingly, in the last recording, for instance, Linda Fregoso uses flagging to amplify the voice of one of the interviewees. The recording of the interviewee speaking Spanish plays and then pauses, at which point Fregoso translates to English the sound bites of the interviewee’s voice recording. In one case, Fregoso states that

In this recording, Fregoso translates part of the interviewee's statement. This represents flagging because Fregoso is emphasizing a particular sound bite which not only summarizes the point of the interviewee but frames its meaning in the larger context of the interview.

Flagging is evident in newspaper clippings, zines, and similar media created at UT during the 1980s education reform movement. Since “the struggle against unequal schools did not end in the 1970s,” and then it “picked up steam in the 1980s,” activists utilized flagging to strategically reference meaning (Murillo 2010). For example DROP OUT is a 1980s zine for students who have or want to drop out of school, which is located in the Center for Mexican American Studies Records (CMAS). One of the contributions begins with “in this land of the free / home of the brave,” and in another contribution, there is purposeful misspelling of words, such as “skkkool” (DROP OUT Zine n.d.; added emphasis). The former calls on readers to associate dropping out with "The Star-Spangled Banner," which brings into association the American values shaping the education system. And, in the latter, “kkk” associates school with the Ku Klux Klan, correlating white supremacy with education. The racism experienced by Latino/a students in the American university—as exhibited by Texas A&M and the University of Texas not meeting minority admissions standards in 1989—is adequately referenced by correlating US Latine activists’ desire to fight against the education system (Trevino 1987). This practice aligns with the “MediaEssentials Training Manual” by positioning flagging as a way to “sum up your message” and clearly indicate “the information you want the audience to take with them” (GLAAD n.d., 25).

This strategy is also present in June 1977, when the Texas Farm Workers Union (TFWU) organized a 1,600 mile march from Austin, TX to Washington D.C., to “give Congress and President Carter a message” (Acosta n.d.; Finch 1977). Marcher George Zargoza utilizes flagging by positioning the sound bite “we produce food for you to eat” alongside “we don’t have enough food to eat” to emphasize the disparity between “you” and “we.” Similarly, the TFWU pins depict the Statue of Liberty waving a flag with the TFWU logo (Texas Farm Workers Union Pins n.d.). Just as Zargoza in the “40 on March to Washington” newspaper clipping references the meaning of “you” and “we,” the TFWU pins quite literally “flags” the meaning of this relationship by referring to the goal of reciprocity between the US (State of Liberty; “you”) and US Latine activists (TFWU flag; “we”). In short, US Latine activists flag the meaning of sound bites by correlating disparate relationships that influence their efforts and goals.

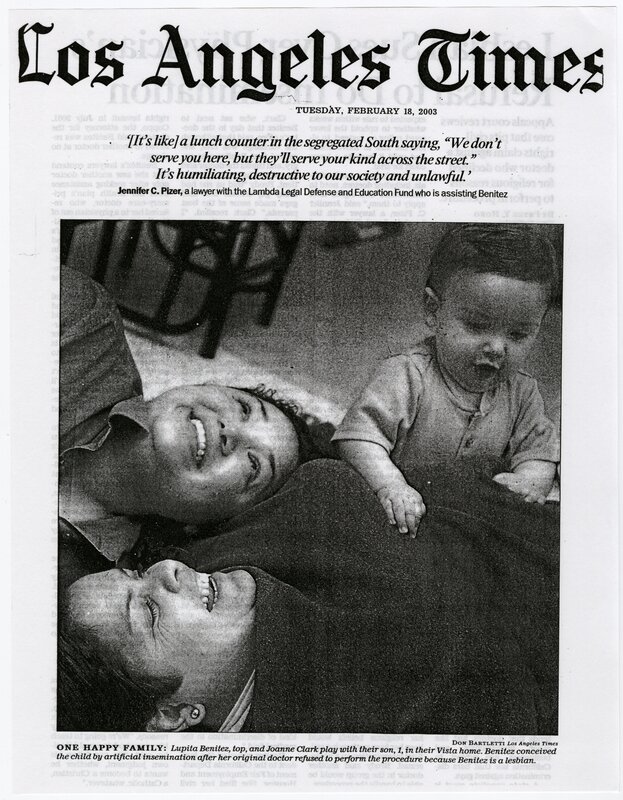

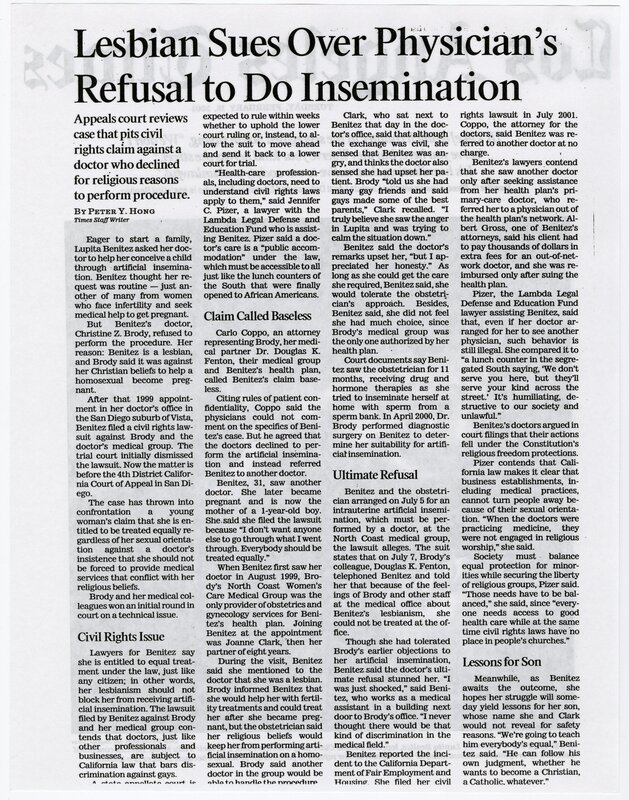

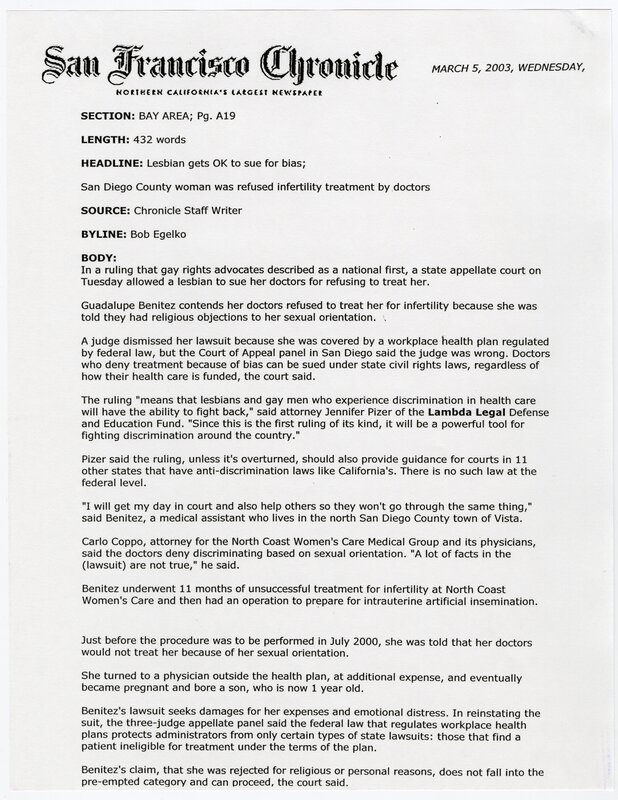

News media in the LLEGO collection, such as Mujerio, newspaper clippings, and journal issues of Viva Arts Quarterly, illustrate how US Latine activists also deploy flagging in LGBTQ+ movements. In both the San Francisco Chronicle and “Lesbian Sues Over Physician’s Refusal to do Insemination,” a woman denied infertility treatment, Lupita Benitez, engages the sound bite, “I will get my day in court and also help others so they won’t go through the same thing,” which is flagged by her own response, “I don’t want anyone else to go through what I went through. Everybody should be treated equally” (Hong 2003). She utilizes flagging in this quote to reference her own altruism which supports US Latine LGBTQ+ reproductive rights.

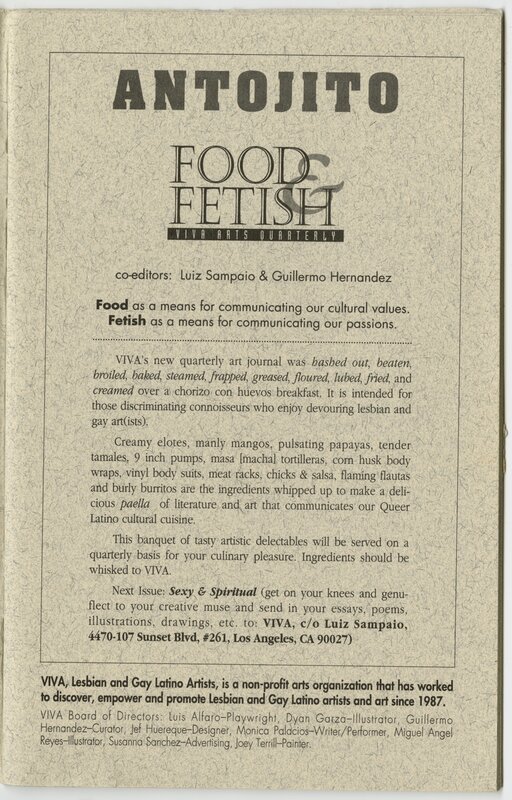

Volume two, Issue one of Mujerio and the Summer 1993 “Food & Fetish” issue of Viva Arts Quarterly respectively reference (1) reproductive rights in the poem “Her Cycle” and (2) food and fetish as a means of communicating “cultural values” and “passions” which are discriminated against (Salazar 1990; Sampaio 1993). This is because both journals reference meanings encoded with gendered and cultural significance to promote the goals of activists. Both are representative of flagging in their foregrounding of meanings which influence their efforts. In print and broadcast media, US Latine activists aptly engage flagging to reference meaningful facets of various movements’ messages to leave readers with concrete and summative goals.

-

Newspaper clipping concerning Lupita Benitez's lawsuit. The page contains a photograph of Benitez, her partner, Joanne Clarke, and their son. —— Recorte de prensa sobre la demanda de Lupita Benítez. La página contiene una fotografía de Benítez, su pareja, Joanne Clarke, y su hijo.

"Lesbiana demanda por la denegación de un médico para realizar la inseminación", página 1

-

Newspaper clipping concerning Lupita Benitez's lawsuit. —— Recorte de prensa sobre la demanda de Lupita Benítez.

"Lesbiana demanda por la denegación de un médico para realizar la inseminación", página 2

-

Quarterly journal on Gay and Lesbian Latine artists. —— Revista trimestral sobre artistas latinos gays y lesbianas.

"Comida y fetiches: Artes Viva Trimestral", página 2

-

Front page of early Mujerio journal issue with an article on its first congress and a poem. —— Portada de la revista Mujerio con un artículo sobre su primer encuentro y un poema.

"Mujerio: Boletín del Área de la Bahía para Lesbianas Latinas", portada

-

Description and transcription of newspaper clipping. —— Descripción y transcripción de recorte de periódico.

Descripción artículo del "Dejan a Lesbiana demandar por parcialidad" en el San Francisco Chronicle