Sound Bites

Sound bites are an essential component of communicating a movement’s message. They are “short, memorable sentences that stand on their own…[and] convey to the audience your organization’s views on an issue” (GLAAD n.d., 20). Further, the subtitle for the “MediaEssentials Training Manual”—which is directly below the title on page twenty—suggests that sound bites function not only to convey information but to influence readers and listeners by “creating effective quotes and getting the audience to care about your issues" (GLAAD n.d., 20). Sound bites, then, function as concise and memorable statements which effectively communicate the meaning of any message to an audience—similar to a thesis statement in an essay. US Latine activists utilize sound bites throughout multiple media to communicate the essence of various goals of civil, labor, and LGBTQ+ movements.

In Onda Latina: The Mexican American Experience—a collection of preserved audio programs at UT Austin—multiple interviewees use sound bites to highlight important topics throughout certain interviews. These sound bites, then, are cut out of context and positioned at various times throughout the audio recording to catch listeners’ attention and frame the show’s narrative. For example, in “Civil Rights and The Texas Police,” after Linda Fregoso introduces the recording, the first three minutes of the audio include an interviewee’s statement:

Per the title of the audio, this sound bite emphasizes and effectively communicates the goals of the recording. Moreover, in this context, interviewees use sound bites by raising their voice during certain words and emphasizing certain sentences—which is common among interviews in this collection. This happens in “The Chicano Movement Today,” when Cervantes, the interviewee, highlights the importance of terms such as "borrowed" and "white" in regard to civil rights tactics used during and after the 1960s. This method of creating a sound bite emphasizes the meaning he is trying to communicate to listeners. So by emphasizing certain terms and cutting out audio and pasting it in other locations, US Latine activists communicate the goals of various movements.

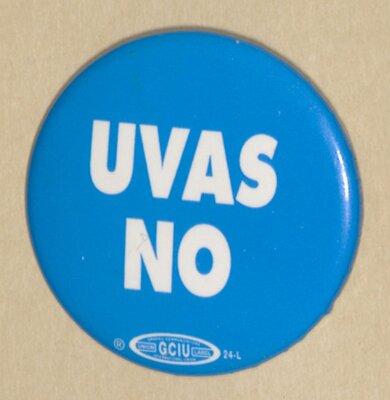

One may also consider slogans as non-auditory sound bites. Pins are a prime example of this, such as those created for the UFW grape boycott, the “most successful consumer boycott in United States history” (Garcia 2013). To promote justice for farm workers by boycotting processed and table grapes, the Texas Farm Workers Union produced pins that display in bold letters “UVAS NO” (in English, “NO GRAPES”) or “BOYCOTT GRAPES,” both with and without the MEChA (Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán) logo of an eagle.(1) The use of concise language next to the logo that represents “self-determination and sovereignty” (Gradilla 2009) allows for the sound bite, “UVAS NO” and “BOYCOTT GRAPES,” to effectively communicate the actions UFW activists sought from their audience. In accordance with the “MediaEssentials Training Manual,” each pin includes elements of “organization or affiliation with the issue in the sound bite” and is able to “personalize the issues” (GLAAD n.d., 21); in this case, rough attachments to personal clothing and materials that enable efficient dissemination and visibility.

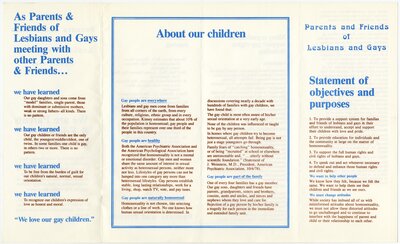

The repetition of these visual sound bites help US Latine activists communicate their efforts. Within the LLEGO collection, items pertaining to PFLAG (Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays) employ this technique to emphasize goals of activists. For example, LLEGO, PFLAG, and LULAC (League of United Latin American Citizens) share similar objectives: to foster “dialogue between the Hispanic and LGBT community, both of whom share a common goal: full equality” (LULAC "Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender [LGBT]" n.d.). This goal is represented in the repeated use of “we have learned” adjacent to “‘we love our gay children’” and the blue subtitles under “About our children" reinforce the shared goals of US Latine activists of/and LGBTQ+ communities (PFLAG n.d.).

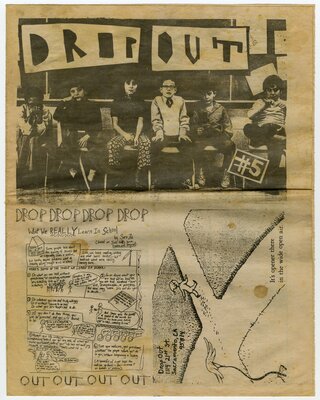

This same repeated use of sound bites, but in “DROP DROP DROP OUT OUT OUT,” is represented in the DROP OUT zine (DROP OUT Zine n.d.). This instance is attempting to communicate the goal of the zine: for students to “DROP OUT” of school. Similarly, a LULAC sticker repeats sound bites which represent US values in the form of the American flag and the term “citizenry” to promote affinity.(2) The sticker depicts colors—in this case, red, white, and blue—and language such as “ALL FOR ONE—ONE FOR ALL” and “60 Years of Commuity Service” [sic] which represent the values of America (LULAC "1929-1989 sticker" n.d.). US Latine activists, in this case, underscore LULAC’s goal to counter racist narratives by associating itself and members with American values. As can be seen in these examples, US Latine activism manifests in sound bites which prioritize repetition and encoded value to communicate meaning.

Textual styling of visual sound bites also emphasize for audiences important takeaways in the movements’ print culture. For example, capitalization in promotional materials helps guide the interest of various readers. This can be seen in early volumes/editions of journals and zines which were developed by and for activists. This includes Viva Arts Quarterly, VOICES for a Compassionate Society, Mujerio: The Bay Area Newsletter for Latina Lesbians, La Mujer: Comision Femenil Mexicana Nacional, Orgullo Latino, MariLes, MICRO-IMPACTO: An HIV Education-Prevention Newsheet from CURAS, and many more. The sheer amount of journals and zines in the mid- to late-20th century represents the determination of activists to utilize print media for the promotion of efforts. Issue one of Gafas Shades: A News Sheet of AUSTIN’S THIRD WORLD LESBIAN/GAY MEN, published in 1980, is organized according to the following sound bites: “RACISM,” “SEXISM,” and “CLASS OPPRESSION.” The capitalization and positioning of these symbolic sound bites preceding the following statement, “These are the issues with which we, as minorities have to deal with every day,” generate a visceral and effective interest which guides the text’s message (Serrano n.d.).

(1) Chicano Student Movement of Azlán

(2) According to the 1929 LULAC Constitution in the “Oliver Douglas Weeks Papers, 1928-1965” at LLILAS Benson, LULAC was to “develop within the members of our race the best, purest, and most perfect type of a true and loyal citizen of the United States” (LULAC "1929 Constitution" n.d.).